Readers should note that this essay substantially reveals the storyline of the film.

When English-speaking audiences discovered Japanese cinema in the early 1950s, it was through a series of acclaimed period dramas including Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon and Kenji Mizoguchi’s The Life of Oharu. Another major critical success of the time was Teinosuke Kinugasa’s vivid drama Gate of Hell. While Kurosawa and Mizoguchi have remained favourites among international critics and film historians to this day, Kinugasa never managed to join them. He sadly came to the global stage too far into his career, his early works ignored and his later ones failing to capture much attention at festivals.

Teinosuke Kinugasa was born in Kameyama in 1896, and started his career not in cinema but in kabuki theatre. He was 17 years old when he ran away from home to join a kabuki troupe in Nagoya, and he made his stage debut two years later.

He specialized in playing female roles, and even as he shifted into acting for film in 1918 he continued to play female parts in screen adaptations of kabuki plays. By 1921 he had started directing narrative films as well as performing in them. The following year he led a mass walkout of the Nikkatsu studios over the company’s decision to start hiring female actors, a decision that effectively killed his and others’ acting careers. He soon established his own film production company, Kinugasa Film Federation, through which he directed several experimental narrative films. The most famous of these was A Page of Madness, produced in 1926.

It’s worth briefly considering A Page of Madness. It was developed through Kinugasa’s membership of the arts group Shinkankaku-Ha – the New Sensationalist Movement. The group was inspired by the influx of new art forms and styles entering Japan via Europe, including cubism, dadaism, futurism and surrealism. These energetic art forms directly inspired Kinugasa’s film, which used hallucinatory flashbacks and dreamlike visuals to tell the story of retired sailor who takes a menial job in an asylum to be close to his mentally ill wife. This silent film was shot without the use of intertitles, and relied on the use of benshi narrating the story in-cinema. The film’s distributor, Shochiku, found it so bizarre and difficult to follow that they only screened it in cinemas usually dedicated to the less popular foreign films. Despite finding some limited success in Europe, A Page of Madness slipped into obscurity. It was only after Kinugasa found an abandoned print in his garden shed in 1971 that the film was re-released and re-evaluated as one of the most provocative works of the 1920s avant-garde.

Kinugasa followed A Page of Madness with Crossroads (Jujiro, 1928), a similarly experimental film about a rejected romance in the Tokyo slums. While most Japanese directors were continuing to draw inspiration from theatrical traditions, Kinugasa was diving head-first into emulating the expressionist films from Germany. His films, while superbly made, simply did not fit into the expectations of Japanese moviegoers at the time, and after Crossroads’ failure the director quietly closed his film company.

Disappointed by the failure of his films to gain proper recognition, Kinugasa packed a print of Crossroads into a suitcase and travelled to the Soviet Union. There he was introduced to noted filmmakers Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin. While touring his film throughout Europe Kinugasa managed to successfully sell its distribution rights in Germany, making Crossroads the first Japanese film to receive a widespread release inside Europe. It subsequently played in cinemas in Paris, London and New York, under the English language title The Slums of Yoshiwara.

Upon his return to Japan, and despite overseas success, Kinugasa found there was still no appetite for his non-commercial, experimental filmmaking. He transitioned smoothly into directing jidai-geki dramas, a genre that dominated the remaining decades of his directorial career. That pretty neatly brings us up to 1953, and the release of his jidai-geki masterpiece Gate of Hell.

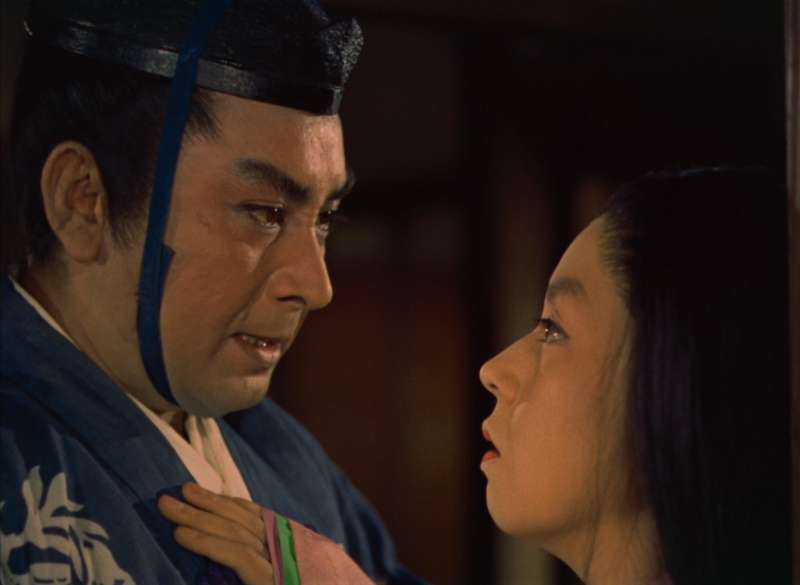

Gate of Hell (Jigokumon) is an adaptation of a stage play by Kan Kikuchi, which was itself drawn from Japanese history. The low-ranking samurai Morito Endo (Kazuo Hasegawa) falls recklessly in love with a lady-in-waiting named Kesa (Machiko Kyo), only to discover she is already married to rival samurai Wataru Watanabe (Isao Yamagata). Morito’s passion will stop at nothing, however, and he soon resorts to stalking, threats and even murder in pursuit of Kesa’s hand.

Gate of Hell was Daiei’s first colour film, although it was not the first to be made in Japan. That honour goes to the comedy Carmen Comes Home, directed by Keisuke Kinoshita in 1951. Gate of Hell was the first colour Japanese film to be released internationally, however, and it made a phenomenal impact on arthouse audiences in the USA and Europe. It was awarded the Palme d’Or grand prize at the Cannes Film Festival – the first Japanese film to do so – as well as the Golden Leopard at the Locarno International Film Festival. It received a 1955 honorary Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in addition to a competitive Oscar for Best Costume Design – Color. Back in Japan, Gate of Hell came and went without anyone really noticing it at all. Internationally, it was a critical smash hit.

To be honest, a lot of the film’s international success came down to timing. Prior to 1950 Western audiences were rarely exposed to Japanese cinema, but the success of Rashomon in 1950 and The Life of Oharu in 1952 stimulated widespread interest. There was an element of novelty about Japanese cinema; audiences were drawn to its distinctive culture and aesthetic, and engaged in a somewhat condescending Orientalist approach. The films that succeeded internationally were inevitably jidai-geki and later chanbara films, which presented a classical, highly stylised version of Japan. Domestic audiences saw these films among contemporary dramas and comedies, while audiences overseas saw them in isolation. They appeared exotic and striking.

In the middle of this growing tide of Japanese films came Gate of Hell, in bright and garish colour, attracting critical attention like a glittering bauble. Even the film’s more ardent fans will readily admit that there were better Japanese films in the 1950s, and better examples of both jidai-geki and early colour cinema. Gate of Hell simply managed to arrive at the right time and attract the interest of the right critics.

Not only was Gate of Hell not particularly acclaimed within Japan – it didn’t make a single end-of-year “top ten” list, for example – its enormous popularity overseas actively angered Japanese critics. There was a sense of territoriality involved, as if Western critics were daring to tell Japanese critics which of their own country’s films were worthy of acclaim. ‘Foreigners,’ wrote one critic, ‘forever souvenir-hunting – always pick Japanese-style paintings on silk rather than our oils on canvas.’[1]

One of the film’s harsher critics in Japan was Kinugasa himself. He intended to direct a much shorter and more tightly edited picture, but studio demands forced him to extend the narrative out and give it a slower pace than he had desired.

The film never really made an impact at home, and while it won a string of awards overseas and played at numerous festivals, it was only very recently that Gate of Hell became available on home video for 21st century audiences to see it for themselves.

For the uninitiated viewer, the opening sequence of Gate of Hell is remarkably confusing. We see an ancient scroll unfold, depicting a violent rebellion in Japan’s past. We are provided with one name after another, as if we should immediately know each mentioned aristocrat or samurai, and with a gravitas that suggests that each person mentioned will be of immense importance in the film to come. Not one of them is.

I cannot say whether or not a Japanese cinemagoer in 1953 would be any more familiar with the historical events mentioned in the introduction. I am guessing the odds must be reasonably good that they were. For those who, like me, find themselves a little overwhelmed: the film opens at the Siege of Sanjo Palace in Kyoto in January AD 1160. Taira no Kiyomori, a military leader who has established Japan’s first samurai-dominated administration, leaves the city on a family pilgrimage. In his absence, two dissatisfied generals – Minamoto no Yoshitomo and Fujiwara no Nobuyori – lay siege to the imperial palace in the hopes of forcing political change. They capture Emperor Nijo, and attempt to also capture his consort, but ultimately both Emperor and consort are successfully smuggled out of the palace by the Taira clan. Upon Taira no Kiyomori’s return the city and the palace are re-taken and Minamoto and his allies are forced to flee.

The opening scenes of Gate of Hell take place during this siege. As Minamoto’s forces flood through the city gates a plan is enacted to smuggle out the emperor’s sister. A samurai loyal to the Taira, Morito Endo, is tasked with escorting a decoy in the hopes that this will confuse the invaders and improve the princess’ chances of escape. While hiding from the invading soldiers, Morito is immediately taken by the beauty of the decoy princess, actually a lady-in-waiting named Kesa, and desires her as his wife.

The siege sequence is presented as a visually stunning sequence of rapid cuts and vivid colour. Anonymous citizens scramble for their lives. Soldiers run in every direction. Banners and woven bamboo curtains are slashed down and trampled. Everything in this sequence is deliberately colourful: red, blue and yellow hues dominate. In one key shot, the chaos unfolds in the background while a group of cocks scrabble in the foreground.

Morito hides Kesa at his brother’s estate, only for his brother to arrive and reveal himself as an ally of Minamoto’s invading army. Morito is forced to oppose his own family to maintain loyalty to Lord Kiyomori.

This opening sequence is a bravura piece of direction, but it’s also a bold act of narrative misdirection, since immediately after the siege is ended the film takes on an altogether different pace, tone and colour palette. I am reasonably certain that it’s this sequence that most impressed the various festival juries and Academy voters around the world at the time of its release. In 1955 noted Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer wrote: ‘Just as the French impressionists were inspired by Japanese woodcut artists, in a similar way there is every possible reason for Western film directors to learn from the Japanese film, Gate of Hell, where the colours really serve their purpose. I would think that the Japanese themselves regard this film as a naturalistic film, in historical costumes, of course, but still naturalistic. Seen with our eyes, however, it seems like a stylised film with attempts at the abstract.’[2]

Dreyer makes a pretty enormous assumption that’s fairly typical of the critical response at the time. He sees the Japanese as culturally naïve, when in fact these sorts of stylised films were seen locally as – if anything – more stylised and unnatural than foreign viewers and critics saw them to be. The most popular Japanese film of 1953, according to critics both then and now, was Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story, a contemporary film about contemporary people. In the same year Kenji Mizoguchi’s A Geisha exploring the post-war plight of Japan’s sex workers. By comparison Gate of Hell is enormously abstract. Dreyer’s perspective comes from the simple fact that Western audiences were responding to jidai-geki so positively that such films were all a Japanese distributor could sell. If all an audience sees of Japanese film is stylised retellings of samurai folklore, that’s all they’re going to think Japanese film is about.

The remainder of Gate of Hell is a passionate character drama shared between three characters. Morito is offered any reward he wants by a grateful Kiyomori: Morito wants Kesa. When he is told that Kesa is already married, Morito doesn’t stop – he simply resorts to more and more disturbing strategies to win her over. Kazuo Hasegawa delivers a very strong performance as Morito. While the majority of his co-stars are still and dignified, he is increasingly harried and kinetic. His performance is deliberately unrealistic and exaggerated. He is breaking social order in attempting to steal away the wife of a more senior samurai, and going so far as to threaten murder to get her, and so Hasegawa’s performance appropriately challenges the style of the actors around him. How Dreyer and his contemporaries ever saw Gate of Hell as in any way naturalistic beggars belief.

Kazuo Hasegawa was a regular collaborator with Teinosuke Kinugasa, and appeared in several of his early films for Shochiku. Like Kinugasa he was a trained kabuki performer who had shifted into motion pictures, and he established a solid reputation and an eager fan base. After leaving Shochiku to work at Toho, a move that deeply angered heads at the former studio, he was randomly attacked by a razor-wielding Korean in the street. The attack left him with a scar on his cheek, and subsequent investigations revealed the Korean was a hired hit man. Whoever hired the Korean was never confirmed. When Kinugasa started directing for Daiei, Hasegawa followed him. His most famous role, Yukitaro in Kon Ichikawa’s An Actor’s Revenge, was made for Daiei in 1963 and marked his 300th film. He died in 1984 at the age of 76.

Machiko Kyo plays Lady Kesa with a blend of dignity and intensity. She is trapped in an impossible position by the men around her: she cannot refuse Morito’s demands without endangering her family, and she cannot accept them without dishonouring her husband. Her solution – to feign complicity in Morito’s attempt to murder her husband, but then to sleep in her husband’s place with Morito makes the fatal strike – is tragic and unavoidable.

At the time of shooting Gate of Hell Machiko Kyo was probably Japan’s most popular screen actress, having already starred in both Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon and Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu Monogatari. She provides a vivid screen presence in Gate of Hell, and elicits enormous sympathy for her character’s impossible position. At the time of writing she is still alive, and has continued to perform sporadically in Japanese theatre.

The third part of this unwilling love triangle is Isao Yamagata as samurai Wataru Watanabe. He is presented as an ideal of the samurai – firm, reserved and calm – and is deliberately staged in contrast to Morito. Yamagata continued to perform well into the 1980s in both film and television. He died in 1996, aged 80.

As Morito’s obsession grows, the colour palette of Gate of Hell subtly transforms. The bright reds and yellows of the early scenes are replaced with deep blacks and blues. Scenes of daylight are replaced by night, as the narrative draws in and changes from period drama to obsessive psychological thriller.

Most striking of all is the film’s dénouement: Kesa’s horrifying solution to her plight has worked. She lies dead in Wataru’s chambers, accidentally run through by Morito’s sword. A shamed and remorseful Morito confesses his crime to Wataru, cuts off his hair as a symbol of his disgrace and begs to be allowed to commit suicide. Wataru refuses: Morito is simply going to have to live with his disgrace and shame. It’s a remarkable conclusion. Wataru does not get visibly upset, nor does he strike or attempt to kill Morito. His dignity is overwhelming, and in denying Morito the escape of ritual suicide he is denying him any chance of forgiveness or redemption of honour. This is the scene that makes the greatest impact on me, because it is so unexpected at first, but so inevitable upon reflection. The film opens on scenes of the most remarkable chaos, and it concludes unhappily but in a state of ordered calm.

It is at this moment that the film ends: the expectations of bushido up-ended but reset, everyone having lost terribly, and two men staring at one another in the moonlight as we slowly fade to black.

[1] Quoted in Joseph L. Anderson and Donald Richie, The Japanese Film: Art and Industry, Grove Press Inc, 1959.

[2] Carl Theodor Dreyer, “Imagination and Colour”, 1955. Translated by Donald Skoller, quoted in Gate of Hell DVD sleeve notes, Eureka DVD, 2012.

Leave a comment