Motion pictures essentially came to Japan in late 1896, with a public demonstration of Thomas Edison’s kinetoscope at Kobe’s Shinko Club. By the end of the century early Japanese filmmakers were experimenting with short films of street scenes and documentary subjects; what the French were already referring to as actualités. Japanese dramatic film arguably started with photographer Shibata Tsunekichi’s short film “Maple Viewing” (“Momijigari”, filmed in 1899 but not exhibited until 1903), but it would not be until December 1910 that Japan generated its first genuine dramatic feature film. That film was Chusingura – sometimes referred to in English as The 47 Loyal Ronin – and its director was Makino Shozo.

On 22 September 1878 Makino was born in Yamakuni village, Kyoto. He may have started life in a modest fashion – the son of a Chinese medicine practitioner and a gidayu theatre performer – but he grew up to become the most significant director of Japan’s earliest cinema. Between 1908 and 1929 he directed an estimated 323 narrative films, an average of more than 15 per year. While most of them are now lost – and thus his work difficult to fully appreciate – more than any other filmmaker in history he influenced the form and genre of the medium in Japan. If there is a poster child for early Japanese cinema, it most surely would be Makino. It is no surprise that he remains popularly known as ‘the father of Japanese cinema’.

In 1901 Makino’s family purchased a Kyoto theatre known as the Senbonza. Refurbishments were delayed when the burning down of a theatre in Shinkyogoku led the government to enact more stringent fire safety regulations. Senbonza finally opened under the management of Makino’s mother in September 1901. It was at the theatre that Makino first worked professionally as an actor, a gidayu, and a director. He later graduated to managing the theatre in his mother’s stead.

In February 1902 Senbonza hosted a theatre troupe led by kabuki actor Onoe Matsunosuke. Born Nakamura Kakuzo, Onoe was the son of a low-ranking samurai that had moved into the house rental business following the Meiji Restoration. Trained from a young age by the noted actor Onoe Tamizo II, he was granted the actor’s family name as an honorific and adopted his more famous performing name in 1892. Onoe and his troupe returned to Senbonza in 1905 and 1909. The relationship he forged with Makino Shozo was a critical one, not only for their respective careers but for Japanese narrative cinema as a whole.

By 1908 Makino’s reputation as both a playwright and a director was strong enough that Yokota Einosuke, co-owner of the Yokota Shokai production company, approached him with an offer to direct a short film. Having already established a reputation for writing plays about Japanese history, Makino made his film debut directing The Battle of Honnoji (本能寺合戦). Cinema was not unknown to Makino at the time, since the Senbonza theatre had already been screening films as a means of supplementing its live theatrical income.

The Battle of Honnoji is a lost work, so we cannot know exactly what it was like or what it was about. Honno-ji was a temple in Kyoto, and the site of a notorious assassination of the daimyo Oda Nobunaga in June 1582. It is this incident that almost certainly provided the basis for Makino’s film. The Battle of Honnoji, therefore, was most likely typical of Makino’s subsequent works. He would enjoy a hugely successful career adapting historical events for film.

The film was shot by cinematographer Ogawa Makita, and starred kabuki actors Nakamura Fukunosuke and Arashi Ritoku. The former was the fifth to assume his name. Born in 1871, he died in 1918 with his son assuming his name as the sixth Nakamura Fukunosuke. The latter, who was born in 1875 and appears to have made his screen debut here, developed an extensive career in narrative film. Between 1908 and 1935 Arashi appeared in 272 films. He died in 1945, aged 70.

The Battle of Honnoji premiered at Nishiki-za Theatre on 19 September 1908, just three days shy of Makino’s 30th birthday.

The genre of films that dominated Makino Shozo’s career – historical dramas of pre-Meiji Japan – would come to be known as jidaigeki. Indeed it was a later Makino production – 1923’s Woodcut Artist – that was first promoted using the jidaigeki label.[1]

Even before the jidaigeki name settled into wide usage, historical films were an immediate hit with domestic audiences. They provided stories that were markedly different from those imported from Europe and America. In addition to establishing a robust national cinema, jidaigeki also allowed for Japanese narrative film to evolve into a more contemporary form. Rather than simply capture traditional theatre performance, those same historical and fictional narratives could be showcased in fresh and stimulating forms. The technical and storytelling possibilities of cinema could be exploited to bring traditional Japanese storytelling into the 20th century.

The Meiji Restoration had been focused on advancing Japanese technology and culture to match the powerful nations in Europe and North America. Jidaigeki films arguably did the opposite: dragging cultural tradition and folklore from before the Restoration into the present, and re-integrating it into a rapidly changing contemporary context.

Makino’s entire career was spent directing silent films. He allegedly relied very rarely on screenplays, shouting direction to his actors instead in a style known as kuchidate. He was also not a technical innovator: his single reel shorts, which dominated his early film works, were typically shot in single long takes without edits. This technique, while simple, was arguably also influential. Similarly long takes can be found among several key second-generation filmmakers, including Mizoguchi Kenji and Shimizu Hiroshi.

Yokota Shokai released two more Makino films in March 1909. The Heavenly Being Sugawara (菅原伝授手習鑑) starred Onoe Baigyo and Ichikawa Shingoro. This early horror film featured the ghost of the 9th-century poet Sugawara no Michizane, who rises to take his revenge on his enemies. It was shot on location in late 1908 at Kyoto’s Kitano Tenmangu shrine. The Pale Crow: Dream of a Light Snowfall (明烏夢の泡雪), also shot in 1908 but held back to the following year, was an adaptation of the final act of an 1851 kabuki play. Two lovers – a courtesan and a samurai – commit a double suicide when they are unable to live their lives together.

On 12 April the Fujikan Theatre in Asakusa, Tokyo, premiered Makino’s fourth film Cherry Blossoms at Kojima Takatoku (児島高徳誉の桜, also translated as Takanori Kojima’s Glorious Cherry Tree). As with The Heavenly Being Sugawara, the film was shot on location at the Kitano Tenmangu shrine. It starred Ichikawa Shinshiro as 14th century noble Kojima Takanori, who carves a Chinese poem onto the trunk of a cherry tree to confirm his loyalty to the exiled Emperor Go-daigo.

Cherry Blossoms at Kojima Takatoku was very much an opportunistic production, made with leftover film stock from Makino’s earlier films for Yokota Shokai.

June 1909 saw the release of Adachihara Third Act: The Scene of the Sodehagi Ceremony (安達原三段目袖萩祭文の場), starring Umegyoran Eijiro, Onoe Baigyo and Makino Tomie. Originally written in 1762 for a puppet theatre by Chikamatsu Hanji, the film presented an excerpt from a story set during the Zenkunen or Former Nine Years’ War.

The following month Yokota Shokai released Sakurada Incident Bloodstain Snow (桜田騒動血染雪). It appears most likely that this film was related to the assassination of Ii Naosuke, Chief Minister of the Tokugawa shogunate, on March 24 1860. If this is indeed the case, it formed the most recent historical inspiration for Makino’s films up to that point – predating the Meiji era by just seven years.

For Goban Tadanobu Genji (碁盤忠信源氏), released in December 1909, Makino finally secured Onoe Matsunosuke to play the lead in one of his films. While Onoe had been performing at Makino’s theatre once again in 1909, the film marked his screen acting debut. To accommodate his evening stage performance, Goban Tadanobu Genji two scenes were shot on the morning and afternoon of 17 October at the Daichoji Temple in Kyoto – close to the Senbonza theatre. The film was based on the play of the same name, itself an adaptation of the Kawatake Mokuami story “The Foundation of Chitose Soga Genji”.

The Makino-Onoe relationship was a fruitful one. The actor appeared in Makino’s Ishiyama War Chronicles (石山軍記, January 1910) and The Origin of the Sanjusangendo Temple (三十三間堂棟由来, March 1910), before starring in Chusingura (忠臣蔵, December 1910).

Chusingura marked Makino Shozo’s 10th film, and was also his longest. While his earlier films had all been short works running to a single reel of film each Chusingura ran to six full reels – his first full-length feature. The film adapted Japan’s iconic “loyal 47 ronin” incident from 1703, a cornerstone of Japanese popular folklore.

The story of the 47 ronin, in brief: the daimyo Asano Naganori is deeply insulted by a court official named Kira Yoshinaka, and assaults him in a temper. As Asano has drawn his blade within the boundaries of the Shogun’s residence – a dishonourable act – he is ordered to commit ritual suicide, and his lands and titles confiscated. Asano’s family is ruined both financially and reputationally, and his samurai retainers are declared ronin: samurai without a master.

While these ronin are dispersed, they do not forget Kira Yoshinaka’s insults. After plotting their revenge for two years 47 of the ronin banded together, infiltrated Edo Castle, and decapitated Kira. Knowing their actions, while consistent with their code of honour, defied the direct command of the Shogun, the 47 ronin surrendered to authorities. After being found guilty of Kira’s murder, 46 of the 47 ronin committed ritual suicide. The 47th, Terasaka Kichiemon, was pardoned – allegedly on account of his youth. When he died at the age of 87, his body was buried alongside his fellow samurai at Edo’s Sengoku-ji temple.

The combination of themes – honour, loyalty, dedication, and sacrifice – made the 47 ronin a hugely popular subject matter in Japanese popular culture. This particularly became the case during the Meiji restoration, where those themes resonated powerfully with a culture undergoing unprecedented change. Literary adaptations of their exploits came to be known as chusingura, which Makino adopted as his title.

Due to the significant gaps in our knowledge of early Japanese cinema, it is impossible to know precisely how many times the chusingura narrative has been adapted to the screen. The number is almost certainly close to one hundred, including such films as Makino’s 1928 version Chukon Giretsu: Jitsuroku Chushingura (忠魂義烈 実録忠臣蔵), Mizoguchi Kenji’s Genroku Chusingura (元禄 忠臣蔵, 1941), Watanabe Kunio’s The Loyal 47 Ronin (忠臣蔵, 1958), Fukasaku Kinji’s The Fall of Ako Castle (赤穂城断絶, 1978), and even loose English language adaptations such as Carl Rinsch’s 47 Ronin (2013) and Kazuaki Kiriya’s Last Knights (2015). Makino Shozo’s 1910 adaptation was almost certainly not the first film version, but in every respect it is the first version that found a large audience.

Chusingura premiered at Asakusa’s Fujikan Theatre in early December 1910. Onoe played the twin lead roles of daimyo Asano Takumi-no-kami and lead ronin Oishi Kuranosuke. The film also featured Kataoka Ichinomasa as Kira Kozuke, Arashi Tachibana Raku as Gengoemon Kataoka, and Ichitaro Kataoka as Oishi Masanori.

The National Film Archive of Japan retains six separate prints of Chusingura of varying lengths and conditions. The shortest version is 42 minutes long; the longest 72. Even the longest print is incomplete, and some scenes have been inserted from subsequent silent adaptations of Chusingura to support what remains of the original film. Understanding why there are so many versions of the film requires familiarity with the ad-hoc, somewhat improvised nature of early Japanese cinema. For modern-day audiences, feature films are essentially fixed objects; that is, once the feature has been edited and distributed its content never changes. In the case of Chusingura, Makino returned more than once in the following months and years to add additional scenes. Local cinemas would also engage in their own enterprising re-edits as well, slipping in scenes from other film adaptations – some of which also starred Onoe Matsunosuke.

At the time of writing Japan’s Meiji Film Archive hosts an online copy of a 50-minute print[2] of Chusingura that can be freely viewed from anywhere in the world. It is this copy that I viewed in preparation for this essay, and it offers a rare chance to see Makino Shozo’s early directing style as well as Onoe Matsunosuke in performance.

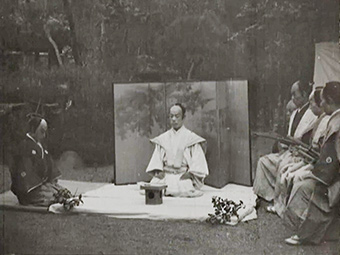

The phrase ‘clarity first, story second’ (‘ichi nuke, ni suji’) would later be used by Makino to describe what he considered best practice in filmmaking. In other words, there was no point telling a story if the audience could not see the action on screen. This attitude dictated much of Makino’s directorial style and aesthetic. The entire film is composed of flat, horizontal scenes captured in long single takes with either natural backgrounds or painted backdrops. Scenes were shot either outside entirely, or in glass-topped studio buildings so as to use natural light. Any additional lighting was placed directly in front of the camera; side-lighting and back-filling for atmosphere were not considerations at the time. If there was a sudden moment of rich visual texture, it was most likely accidental.

In his book The Aesthetics of Shadow: Lighting and Japanese Cinema, film historian Miyao Daisuke notes the lighting of the opening scene from a 1911 print of Makino’s Chusingura: ‘Strong lighting from the top creates dark shadows of the men and a pillar on fusuma screens in the background. It is possible to interpret that the lighting of this shot emphasises the authoritative characteristic of the men. But it is more reasonable, rather, to read the dark shadows as an inevitable consequence of shooting on a glass stage. The cinematographer was probably not able to achieve consistency in the supply of sunlight.’[3]

The online copy consists of 13 scenes of varying lengths, most of which are derived from the kabuki play The Treasury of Loyal Retainers (仮名手本忠臣蔵). Both the play and the general story of the 47 ronin were very well known among the viewing public. Makino could have been confident his audience knew the plot, and could therefore focus on the scenes he wanted to include without concern that his film would be confusing.

This, of course, can make Chusingura particularly confusing for a 21st-century audience that does not know the play, nor the conventions of kabuki theatre that inspired the performance style, and does not have the benefit of a benshi at their side providing all of the narration and dialogue.

Chusingura begins with a brief prologue scene of samurai outside of some castle gates. Its first full scene – and the longest in this version at 10 minutes – broadly replicates the fourth of eleven acts from the play. Lord Asano, having struck Lord Kira in a temper, is questioned on his motives before the Shogun arrives to pass sentence for his crime. His is to commit seppuku – ritual suicide – and his lands and assets are to be confiscated. His retainers are to be disbanded, and must live as masterless ronin.

The fourth and fifth scenes detail Asano’s chief retainer Oishi Kuranosuke receiving the news of his and his men’s fate, and reporting to them. He then surrenders Asano’s estate to the authorities, weeping as he does so.

Scene 5 was shot on location, using the south-west tower of Kyoto’s Nijo Castle to represent Asano’s estate.

The sixth scene, starting at 24:35, adapts Act 7 of the play. Kira’s spies suspect Oishi might be planning an insurrection or revenge attempt, and confront him in an inn in Kyoto’s Gion district. Oishi deliberately embarrasses himself, feigning both drunkenness and dishonourable behaviour to throw the spies off the scent.

To be honest, later scenes become more difficult to follow. Oishi travels to Edo in disguise as a palace official named Tachibana. Upon arrival he accidentally bumps into the real Tachibana, who then feigns being the imposter to preserve Oishi’s disguise. The 47 ronin dine together at a soba restaurant before heading to Kira’s residence; they find him cowering inside a coal shed. The final scene – commencing at 45:10 – depicts the 47 loyal ronin bringing the assassinated Lord Kira’s head to the Sengaku-ji temple where Lord Asano was buried. A painted backdrop stands in for the real Sengaku-ji, which is located in the Tokyo suburb of Minato. At 47:30 Kira’s severed head makes an appearance, taken out of a bag and offered to Asano’s grave. At the film’s conclusion, the ronin collectively prepare to commit seppuku.

Over the remaining two years of the Meiji era, Makino directed at least 10 other films. Shikanosuke Yamanaka (山中鹿之助) and The Legend of the Righteous People of Akita (秋田義民伝) were released in June 1911. Jutaro Iwami (岩見重太郎) followed in August 1911, Yataro Sekiguchi (関口弥太郎) in September, Jirocho of Shimizu (清水の次郎長) and Revenge at Sozenji Baba (敵討崇禅寺馬場) in October, and Ieyasu (The Story of Tokugawa Eitatsu) (徳川栄達物語) in November.

Makino and Onoe collaborated on an additional 43-minute short feature of Chusingura that premiered in February 1912. The Life of Shiobara Tasuke (塩原多助一代記) followed in May, and Jirozaemon Sano (佐野次郎左衛門) premiered on 15 July. This latter title was likely a biographical adaptation of the early 18th century farmer of the same name, who fell in love with a courtesan in 1720 Edo before allegedly murdering both her and her lover in a fit of jealous rage. The film marked Makino’s final work released during the Meiji era.

Despite shifting into educational films later in life, he remained attracted to the 47 ronin story. He directed several more adaptations, including Kanadehon Chusingura (仮名手本忠臣蔵, 1917), The True Story of Chushingura (実録忠臣蔵, 1922) – the first to actually record on location at Ako Castle – and Heroism of the Faithful Dead: True Testament of the Chushingura (忠魂義烈 実録忠臣蔵, 1928).

A year after the latter release Makino Shozo died, aged 50. Filmmakers who owed their careers to his support include Tomu Uchida (Bloody Spear of Mt Fuji), Teinosuke Kinugasa (A Page of Madness, Gate of Hell), Futagawa Buntaro (Orochi), Numata Koroku (Kosuzume Pass), and Kyotaro Namiki (Beniya Komori). Even within his own family, he exerted considerable influence: of his five children, three became directors in his footsteps while a fourth became a producer. Even today his family remains linked with popular entertainment; his great-granddaughter is the idol singer Anna Makino, who performed in the pop group Super Monkey’s from 1991 to 1993.

[1] Joseph L. Anderson and Donald Richie, The Japanese Film: Art and Industry (expanded edition), Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2018.

[2] https://meiji.filmarchives.jp/works/05_play.html

[3] Miyao Daisuke, The Aesthetics of Shadow: Lighting and Japanese Cinema, Duke University Press, Durham, 2013.

Leave a reply to 10 great old films I discovered in 2025 – FictionMachine. Cancel reply