Iain Softley’s 2005 thriller The Skeleton Key has a queasily uncertain relationship with race, and I honestly cannot decide if it has stumbled into being unexpectedly clever about it or if it is simply so fearful of setting a foot out of place that the race issues are simply a familiar elephant in the room. Delving into this aspect of the film will necessitate digging around the plot and explaining things better left discovered in the viewing, so in brief it seems a half-decent supernatural thriller set in the outskirts of New Orleans that never does anything egregiously bad – but at the same time never quite excels at any individual aspect. It is one of those films that are simply there; entertaining enough in the moment, but hardly worth revisiting in the future.

Iain Softley’s 2005 thriller The Skeleton Key has a queasily uncertain relationship with race, and I honestly cannot decide if it has stumbled into being unexpectedly clever about it or if it is simply so fearful of setting a foot out of place that the race issues are simply a familiar elephant in the room. Delving into this aspect of the film will necessitate digging around the plot and explaining things better left discovered in the viewing, so in brief it seems a half-decent supernatural thriller set in the outskirts of New Orleans that never does anything egregiously bad – but at the same time never quite excels at any individual aspect. It is one of those films that are simply there; entertaining enough in the moment, but hardly worth revisiting in the future.

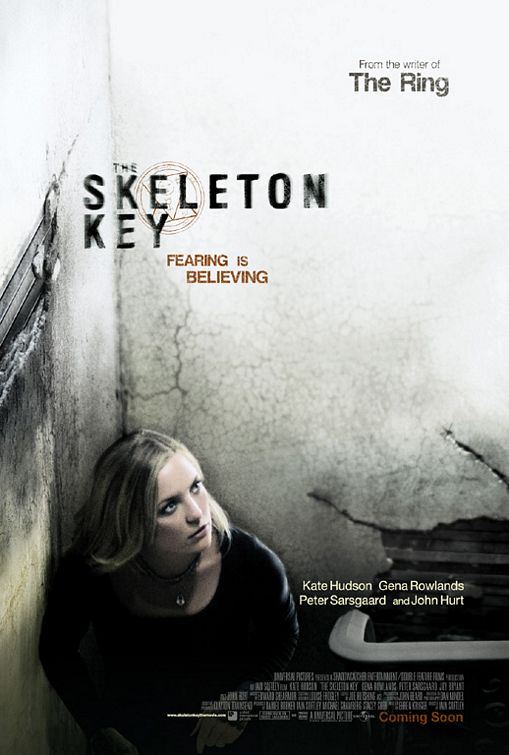

Caroline (Kate Hudson) is a hospice nurse hired to care for a terminally ill patient named Ben (John Hurt). He is purported to be the victim of a severe stroke, however Caroline grows to suspect she is being lied to by Ben’s defensive wife Violet (Gena Rowlands). She also grows obsessed with a secret room in the attic, the door to which is locked despite her possessing a skeleton key supposed to unlock every door in the house.

When The Skeleton Key was released theatrically, it was in a year in which survival horror very much ruled the screen genre in America. Nestled among the likes of Neil Marshall’s The Descent, Rob Zombie’s The Devil’s Rejects, Eli Roth’s Hostel, and Darren Lynn Bousman’s Saw II, The Skeleton Key failed to engage the zeitgeist and suffered remarkably poor reviews. Over the last decade-and-a-half it has actually aged remarkably well; fashions change, and supernatural thrillers inevitably fall in and out of fashion. Iain Softley – an idiosyncratic filmmaker whose works include Backbeat (1994) and Hackers (1995) – keeps up a familiar misty tone to the proceedings, which fall very comfortably into an overall milieu of New Orleans-set horror. The setting may lead genre veterans to predict certain plot twists in advance; it is a faithful variation on the ‘Southern Gothic’ genre, but not exactly an inventive one. Individual moments and jumps are effective and entertaining, while performances by Hudson, Rowlands, and Peter Sarsgaard are all rock-solid (poor John Hurt is playing a mostly paralysed man, so hardly gets a chance to shine).

There is an interesting conundrum at the centre of the film, however, and to its credit it lets The Skeleton Key become a much more interesting movie in retrospect than it was during the actual watching of it. We learn quite early into the piece that the locked attic room contains the paraphernalia and artefacts of Mama Cecile (Jeryl Prescott) and Papa Justify (Ronald McCall), two magic-performing people of colour who worked the house as servants in the 1920s before being violently lynched by their white employers. This back story raises a lot of immediate eye-rolling problems. It is a New Orleans horror story. Of course there is an play of the ‘magical negro’ trope. Of course there is a lynching in the back story. Of course there is a white-owned plantation house, and an overall miasma of unaddressed moderate racism to the picture. People of colour are mentioned but largely not seen (a throwaway line discusses how the African-American nurses never stay at the house) or they are used to drive a ghost story plot but do not get properly given agency themselves. Racism gets exploited for horrific thrills when a flashback shows off a double lynching at the hands of jeering white socialites. And then the ending comes, and it is like everything has been thrown into a blender.

The climactic revelation, that Cecile and Justify used magic to jump from their bodies to those of two white children before the lynching, and subsequently to the bodies of Ben and Violet in the 1960s, spins the film’s treatment of race to a dizzying extent. Cecile and Justify’s lynching was portrayed as the murder of two innocent people – except now it is apparent that they were far from innocent, even if the hanging of their bodies is a hate crime. At the same time the problem of the film relying on its black characters without giving them a voice is partly rendered moot – Violet and Peter Sarsgaard’s real estate lawyer Luke Marshall were Cecile and Justify the whole time. Even though the characters are secretly present throughout, they are not performed by actors of colour – so is the black experience represented or not?

Taken with as little cultural context as possible, it is a neat little twist and a solid ‘shocker’ ending to a horror story. When inserted back into the overall experience of African Americans in popular cinema, and race issues in Louisiana, it is much more difficult to decide whether The Skeleton Key is mildly offensive or nicely provocative – or for that matter if it is dreadfully silly or actually quite smart. I suspect it might just be the former for one and the latter for the other – someone in Hollywood figured out how to tell a black story without any black people in it.

Leave a comment