Two engineers turned entrepreneurs, Aaron and Abe, attempt to build a machine that can defy gravity. Instead they accidentally build a box which outputs more power than they put into it, and within which time appears to run backwards. When they build a much bigger version of the same box, they are able to climb inside and – to their surprise and delight –travel back into their own past.

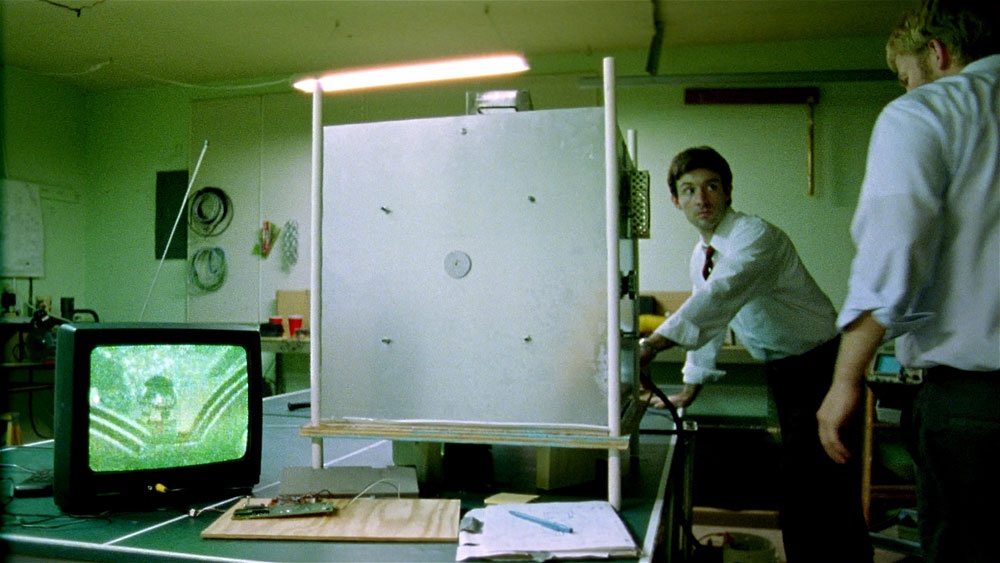

Primer is a low-budget science fiction drama written and directed by Shane Carruth, who also co-stars as one of the hapless engineers. It was a cult and critical sensation on release, primarily because of its budget. When I write ‘low-budget’ I mean it: Shane Carruth produced Primer for roughly $7,000.

While the film is extraordinarily impressive given its inexpensive origins, it’s also extraordinarily impressive in its own right. It is quite simply one of the best science fiction films ever made: a literate, clever and ultimately quite frightening time travelling thriller. It takes one watch to impress the viewer, but many more viewings for its complex, recursive narrative to become clear. It is the most satisfying kind of film: the kind that gives up more to its audience with every successive viewing.

Shane Carruth was a software engineer with a passion for story. He developed this passion while studying mathematics at university, writing short stories and even attempting to write a novel. After a while he shifted from prose to script. ‘I guess this is just like this thing that’s been growing since college,’ he admitted. ‘I moved to screenplay format and then it was just a matter of time before I wondered if it was possible to execute one of these things.’ [1]

Carruth’s screenplay wound up focusing on a pair of inventors, and the ethical quandaries that their discovery would create. ‘I always knew what the story was thematically,’ said Carruth, ‘before it turned into science fiction. It would be about trust and how that’s linked to what’s at risk. I was reading about innovation and that’s where I got the setting.’ [2]

Carruth wrote his screenplay over a 12 month period. ‘I found myself reading a lot of books that had to do with discoveries. Whether it involved the history of the number zero or the invention of the transistor, two things stood out to me. First is that the discovery that turns out to be the most valuable is usually dismissed as a side-effect. Second is that prototypes almost never include neon lights and chrome. I wanted to see a story play out that was more in line with the way real innovation takes place than I had seen on film before.’ [3]

While reading a book by noted theoretical physicist Richard Feynman, Carruth hit upon the idea of having his two entrepreneurs accidentally invent a time machine. ‘Richard Feynman has some interesting ideas about time,’ said Carruth. ‘When you look at Feynman diagrams [which map the interaction of elementary particles], there’s really no difference between watching an interaction happen forward and backward in time. That’s something I got interested in early on.’ [4]

Carruth said: ‘There’s almost no time travel-related science. What they’re trying to do at the beginning, degrading gravity using superconductors – that was technically researched. The point where it goes from saying we’re doing such an efficient job degrading gravity that we’re also blocking time – that’s the leap. But there are plenty of stories in the history of innovation where you’re heading towards one thing and there’s a side effect that turns out to be the valuable thing, like John Bardeen’s accidental invention of the transistor.’ [5]

Carruth titled his screenplay Primer. ‘I saw these guys as scientifically accomplished but ethically, morons,’ he explained. ‘They never had any reasons before to have ethical questions. So when they’re hit with this device they’re blindsided by it. The first thing they do is make money with it. They’re not talking about the ethics of altering your former self. So to me, they’re kids, they’re like prep school kids basically. To call it a primer or a lesson was the easy way to go.’ [6]

Time travel has been a rich source of science fiction stories for over a century. While there were certainly earlier cases of fiction characters travelling into the future, by magic or supernatural means, it was H.G. Wells’ 1895 novel The Time Machine to popularised the concept. In that book, Wells’ protagonist constructed a time machine and used it to travel eight hundred centuries in the future. In 1960 director George Pal adapted the novel into a popular motion picture, and that film has been followed by a string of time travel adventures, some serious and some whimsical.

The treatment of time travel in motion pictures has varied wildly. For some films, such as Harold Ramis’ Groundhog Day (1993), time travel exists purely as a narrative device: protagonist Phil Connors experiences the same day over and over as an unexplained means of teaching him to become a better person. In others, such as Robert Zemeckis’ overwhelmingly popular Back to the Future (1985) time travel forms a core part of the narrative, and much of the film is spent exploring the potential ramifications of changing history and creating time paradoxes (changing the past prevents the present-day protagonist from existing, therefore removing his ability to change the past).

Where Primer varies considerably from the majority of time travel movie is the incredibly logical and scientific way in which it has treated the concept. As a mathematician and software engineer, Carruth has approached time travel with a rigorous eye for detail and mathematical sense. Aaron and Abe do not construct a magical box that can somehow transport them into the past or future. All they have invented is a box within which time is travelling in the opposite direction. Climb inside, and you can travel back into the past, but you can only travel back one minute in history for each minute you stay within the box. To travel back six hours, as they begin to do in the film, Aaron and Abe have to turn the machine on, leave it alone, come back in six hours, climb inside, wait another six hours, and then climb out shortly after their original selves left the box alone. It’s time travel on an unexpectedly modest scale, but it’s a scale with which Carruth works wonders. The bulk of Primer is dedicated to what would actually happen if you could travel back in time, and all the various options available to a time traveller.

At the point where one of the protagonists realises that you can build two time travel boxes, set one up, go back in time inside that first box with the disassembled second box with you, then build that second box, set it up, and go back to the same point in time again – well, at that point Primer explodes into an Escher-like mess of duplicate people, changing timelines and increasingly desperate behaviour. It is a film told by an unreliable narrator, but unlike a text where the narrator is unreliable through denial (David Fincher’s Fight Club) or deliberate deception (Taylor Hackford’s Fallen), Primer’s narrator is unreliable because he himself is no longer 100 per cent aware of what the hell is going on.

Carruth embarked on producing Primer with no formal training in filmmaking and no prior experience in film production or script writing. ‘Cinematography was incredibly foreign to me,’ he said, ‘so I read as much as I could about it. Once I figured out that it was just photography with a set shutter speed, I got some slide film and I just went about storyboarding the script and taking snapshots. I took a ton of time doing it just to make sure I knew exactly what I was doing.’ [7]

Casting the film was also a difficult process, since with the entire budget committed to production costs there wasn’t any money with which to pay his actors. Anybody who performed in Primer did so in the hope that they would be paid via the ‘back end’ if the finished movie was a success.

Carruth said: ‘I had a bad casting process. It doesn’t sound like a lot, but I auditioned over 100 guys for the two leads, and I found David Sullivan as the other actor but it was a terrible process. I wasn’t offering anybody any money, but the guys who were showing up wouldn’t look at the material beforehand. What I’d have is guys reading off the page… I can’t tell anything from that. It scared me to death – here’s a guy who’s not even prepared for the tryout and if I cast him and he decides to skip out after two weeks, I’m dead.’ [8]

Carruth’s solution was typical of his approach to filmmaking. As he had David Sullivan ready and willing to play Abe, Carruth simply played the role of Aaron himself. Once again he took up a role for which he had no prior training or experience – just an enthusiasm and drive to get his film completed.

Co-star David Sullivan was almost as inexperienced as Carruth. ‘I honestly didn’t know what I was doing,’ he said. ‘I had done a couple of one-act plays in high school playing 60 year-old men, so the kind of acting that was necessary from Primer was something that I was completely uneducated on. I had read the script a number of times and though, very short, it was very wordy and complicated. I knew that the only way we were going to pull this off is if we sounded like we knew what we were talking about, and played it very natural and conversational.’ [9]

The production shoot lasted for roughly two months. Primer was shot on location in Dallas, with Carruth’s parent’s home standing in for many of the scenes. Unlike the majority of ultra-low budget features, which are generally shot using digital video, Primer was shot entirely on Super 16mm film. By choosing this format Carruth faced severe financial restrictions. On a production budget of only $7,000 shooting on film left him with enough money for one take of each scene: if a shot didn’t work, he simply couldn’t afford to try a second time. He also calculated that he would have enough footage to shoot a maximum of 80 minutes. The final edited film is 77 minutes long.

Watching Primer with the knowledge of this restriction is a revelatory experience, because despite a near-insurmountable challenge Carruth continued to shoot Primer as a conventional feature film. There are tracking shots, unexpectedly long takes and scenes of complex, jargon-filled dialogue. It is a testament to Carruth’s preparation, production savvy and sheer talent that the film is as slickly produced as it is.

Carruth meticulously storyboarded every shot of the film before he commenced shooting, and used 35mm photographs for his storyboards so that he could experiment with lighting set-ups at the same time. The lighting of Primer is genuinely impressive: the whole film has a sort of queasy green glow to it that produces a wonderfully uncomfortable effect.

Since Primer was by-and-large a one-man operation, it took Shane Carruth another two years to undertake the editing and post-production necessary to finish the film. ‘I did give up,’ the director admitted. ‘I gave up at least three times during the two years. It took two years to edit and compose and loop and foley and all that. There’s at least three times… It really got to me when someone asks what I did for a living and I realized I didn’t have a good answer. And it was just, I don’t know, it was like I’m in my apartment alone all day editing this thing that I’m calling a film but it wasn’t actually a film yet.’ [10]

When Primer was finally unveiled in early 2004, it made an immediate impact. The Sundance Film Festival awarded it to Grand Jury Prize, an honour previously bestowed on films such as Public Access (1993), Welcome to the Dollhouse (1996) and American Splendor (2003). Independent distributor ThinkFilm negotiated the distribution rights, releasing the film in a limited release across the USA. Carruth’s $7,000 movie ultimately grossed more than $400,000 in select screenings in America.

What makes Primer succeed is not its clever presentation of time travel or its near-incomprehensible narrative: it is its strong focus on character. This is a film about responsibility and trust. Abe and Aaron may have had the technical ability to stumble upon time travel, but they lack the ethical understanding of how to use that technology – or indeed to determine if they should use it at all. In this respect Primer essentially tells the oldest science fiction story there is: the Promethean struggle to control the natural world, only to fail spectacularly through foolishness and hubris.

Thankfully the dangers presented in Primer seem unlikely to occur in the real world. ‘For a while I believed that asking to travel in time was too much,’ Carruth admitted, ‘but I could almost believe that you could send information. It took a year to write the film and by the end of it – I probably shouldn’t say this out loud – I have a sort of proof that it can’t exist. If you buy that it exists, it means something more profound about where we live. It means we don’t live where we think we live.’ [11]

REFERENCES

- Rebecca Murray, “Primer – Shane Carruth interview”, About.com, 21 October 2004.

- Dennis Lim, “A Primer Primer”, Village Voice, 5 October 2004.

- Shane Carruth, Primer production notes, 2004.

- Lim, 2004.

- Lim, 2004.

- Wendy Mitchell, “DVD re-run interview: Shane Carruth on Primer”, Indiewire, 18 April 2005.

- Mitchell, 2005.

- Mitchell, 2005.

- Quoted in “Exclusive Interview: David Sullivan”, Live for Film, 8 December 2009.

- Murray, 2004.

- Lim, 2004.

Leave a comment