17 April, 1980: Walt Disney Productions releases its latest feature film, The Watcher in the Woods. It is directed by John Hough, who helmed the company’s 1970s hit film Escape to Witch Mountain (1975) and its sequel Return from Witch Mountain (1978). Despite their titles, those films were family-friendly science fiction. The Watcher in the Woods is, by contrast, Disney’s first self-proclaimed attempt at supernatural horror.

10 days later, Disney abruptly yanks The Watcher in the Woods from release. The film does not emerge for another 17 months when, in October 1981, it returns to cinemas. It has been re-shot in places, re-edited throughout, and – after grossing a meagre five million dollars – sinks without a trace.

The string of Walt Disney films released between 1979 and 1985 reflected a desperate attempt by the company to reclaim cultural relevance and commercial success in a film industry that had been wholly up-ended by the blockbusters of the 1970s. Of all of Disney’s post-Star Wars attempts to reclaim their audience, it seems like that The Watcher in the Woods was their least successful.

Jump back about three years, to producer Tom Leetch. He was a career producer at Walt Disney Productions, whose participation in the company dated back to being assistant director of Mary Poppins in 1964. He also worked as assistant director on The Ugly Dachshund (1966) and Monkeys Go Home (1967). As a producer he contributed to The Boatniks (1969), Napoleon and Samantha (1972), and Freaky Friday (1976).

When Leetch discovered Florence Engel Randall’s novel A Watcher in the Woods (1976), he immediately considered its potential as a new Disney feature. He knew that the company was struggling in the wake of “New Hollywood”, and that studio head Ron Miller was actively looking for more adult and mature material. Randall’s novel related the story of a teenage protagonist who moved to a country house near the woods. There was a legend of a missing girl, and a mysterious presence that seemed to live among the trees. Leetch brought the novel to Miller, reportedly telling him enthusiastically that ‘this could be our Exorcist”.[1]

Disney’s The Exorcist sounds as farcical an idea now as it must have seemed to many then, but when considering the shape of American popular entertainment in the late 1970s the concept is perhaps not so far-fetched. Horror films were once thought of as low-budget cult cinema for a fringe audience, but William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973) had opened a massive mainstream market for the genre. The Warner Bros picture grossed US$193 million on release and had received an Oscar nomination for Best Picture. By contrast, the most successful horror film of 1972 was likely Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left, which grossed just over US$3 million.

The success of The Exorcist did not go unnoticed. In the ensuing years, Hollywood’s key studios released Jaws (1975, Universal), The Omen (1976, 20th Century Fox), The Amityville Horror (1978, MGM), Halloween (1978, Compass International), and numerous other horror works. Even an independent film like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) managed to gross in excess of US$30 million.

By the late 1970s horror was big business, and Walt Disney Productions was easily the largest industry player without any skin in the game.

To adapt Randall’s novel into a screenplay, Leetch hired British writer and producer Brian Clemens. While his film credits were largely confined to pulp fare like The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1972) and Captain Kronos: Vampire Hunter (1974), on television he had been enormously prolific. In the UK he had written for The Invisible Man, Francis Drake, Danger Man, and most notably The Avengers – for which he had also worked as script editor and producer.

Knowing Clemens’ work for British independent Hammer Studios, who released an enormous number of horror movies for the British and American markets, makes it unsurprising that his completed draft was much bleaker and more violent than expected. The studio went to dramatist Rosemary Anne Sisson, who had previously undertaken rewrites on the 1977 Disney caper Candleshoe, to lighten the mood and lessen the screenplay’s impact. Rewrites were also undertaken by screenwriters Harry Spalding and Gerry Day (The Black Hole).

In the end, the Watcher in the Woods screenplay was irrevocably compromised by the internal struggles that were crippling the studio at large. Some stakeholders wanted to push the envelope of what a Disney film could present and contain, while others refused to risk losing what cache the Disney brand still held for quality family entertainment. To Tom Leetch and Ron Miller, a Disney horror film must have seemed a provocative, attention-grabbing idea. To the studio executives at large, it was clearly a step that could never be fully taken.

Disney purchased the screen rights to A Watcher in the Woods in November 1978, originally with an intention to adapt it as a made-for-television film. After nine months of development that plan changed, and with production commencing in England, an additional payment was made to Randall to license the book as a theatrical feature instead. The title was also changed slightly, to the more definitive The Watcher in the Woods.

In the lead-up to production, reports in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter suggested that 14-year-old actor Diane Lane had been cast in the lead role. This turned out not to be the case, with figure skater turned actor – and Golden Globe nominee – Lynn Holly Johnson playing the role instead.

Disney appointed British filmmaker John Hough to direct the picture. In a 2013 interview, Hough said ‘I wanted to work for Walt Disney because the films they make at Disney studios last for many decades. And that’s very true: even today, people still come up to me and say, “Thank you for Escape to Witch Mountain and Return from Witch Mountain”.’[2]

In addition to his two Witch Mountain films for Disney, Hough had also directed – among other things – the 1973 supernatural thriller The Legend of Hell House and the 1974 road movie Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry. He was, all in all, a creditable choice: an accomplished director with a strong visual eye, and experience in both horror and working with Disney.

The Watcher in the Woods entered production in August 1979. Studio sequences were shot at Pinewood in London, with location filming taking place in Buckinghamshire and Warwickshire. St Hubert’s Manor, a large estate close to Iver Heath, stood in for the Curtis family’s vacation home. Ettington Park Manor near Stratford Upon Avon, was used for the character John Keller’s home as well as an old chapel.

The film begins with the American Curtis family arriving at an English manor house that they have rented out for the Summer. The manor is in a rural area, and surrounded by dense woodland. It is owned by the elderly and reclusive Mrs Aylwood, who resides in the small cottage next door.

David McCallum and Carroll Baker played parents Paul and Helen Curtis. Baker, an Oscar nominee for her performance in Elia Kazan’s Baby Doll (1956) had appeared in a number of popular Hollywood features, including Giant (1956), The Big Country (1958), and Cheyenne Autumn (1964). In 1966 she relocated to Italy, where she starred in a string of gory giallo and horror films including four for director Umberto Lenzi. The Watcher in the Woods very much represented Baker’s return to American cinema after years spent acting in Italy, the UK, and Mexico.

McCallum was, of course, still best known for his role as Russian spy Ilya Kuryakin in the popular television series The Man from UNCLE (1964-68). More recently he had appeared in the USA/UK co-production Colditz (1972-74), prime-time drama The Invisible Man (1975-76), and the British science fiction serial Sapphire and Steel (1979-1982) opposite Joanna Lumley.

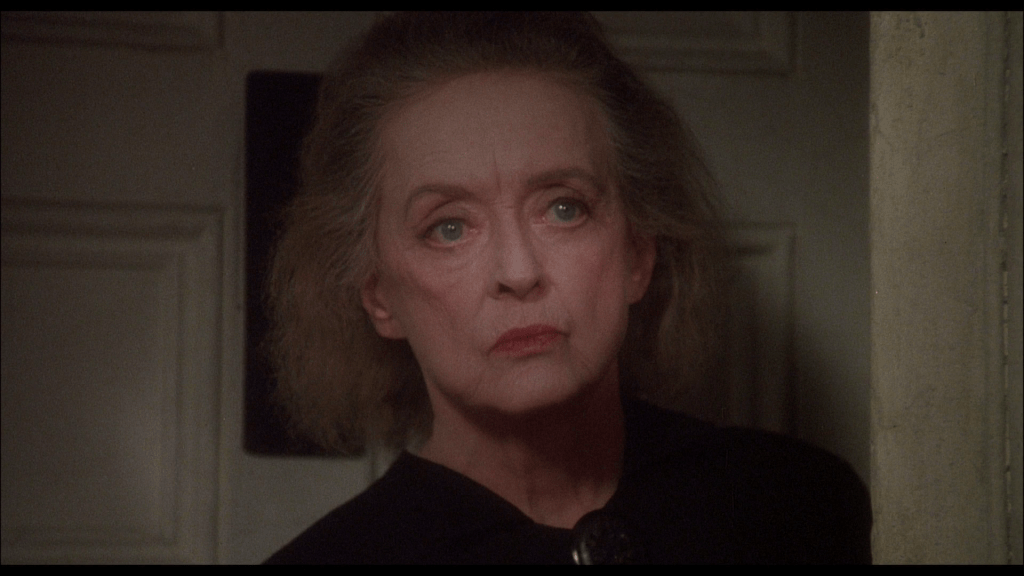

Mrs Aylwood was played by Hollywood legend Bette Davis. Born Ruth Elizabeth Davis in Massachusetts in 1908, she had established a strong and enduring reputation as one of American cinema’s most talented performers. A two-time Oscar winner – and ten-time nominee – she first appeared in Hobart Henley’s pre-Code drama Bad Sister (1931). The Watcher in the Woods would mark her 85th feature film role. In between the two films she starred in Of Human Bondage (1934), The Petrified Forest (1936), Jezebel (1938), The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939), Now, Voyager (1942), All About Eve (1950), Pocketful of Miracles (1961), Hush Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964), and The Nanny (1965). It is not a surprise that The Watcher in the Woods was her first film for Walt Disney Productions; such a distinguished and respected actor would rarely be attracted to starring in a children’s film.

Few summed up Davis’ screen appeal as effectively as the author Graham Greene, writing in 1936 that ‘even the most inconsiderable films […] seemed temporarily better than they were because of that precise nervy voice, the pale ash-blonde hair, the popping neurotic eyes, a kind of corrupt and phosphorescent prettiness.’[3]

John Hough recalled: ‘When I worked with her, I knew exactly what I wanted to do on the set. I always come on the set very prepared. […] Bette Davis really appreciated that I was very strong in what she was going to do in any of the scenes. She enjoyed that because it fully made her free to do her own interpretation within that sort of situation.’[4]

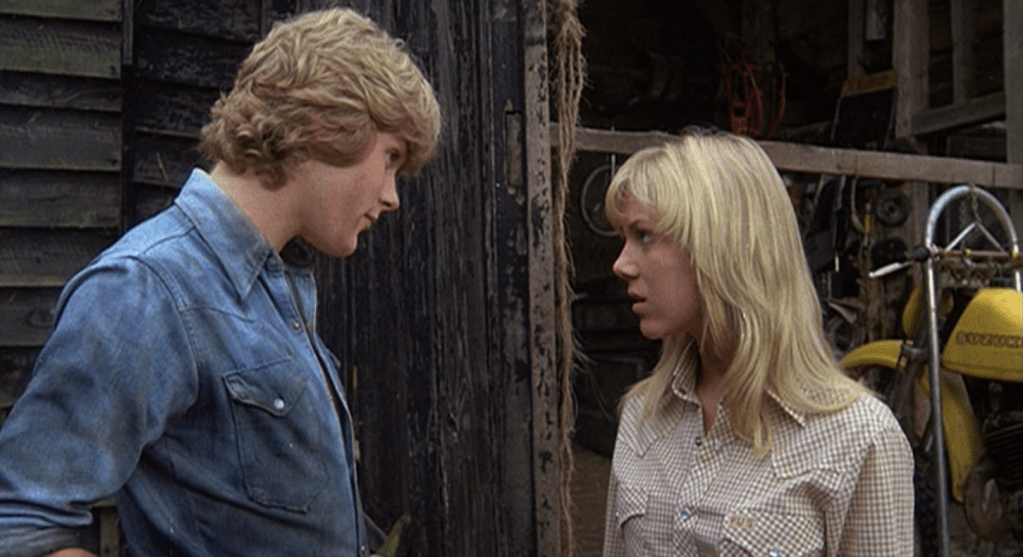

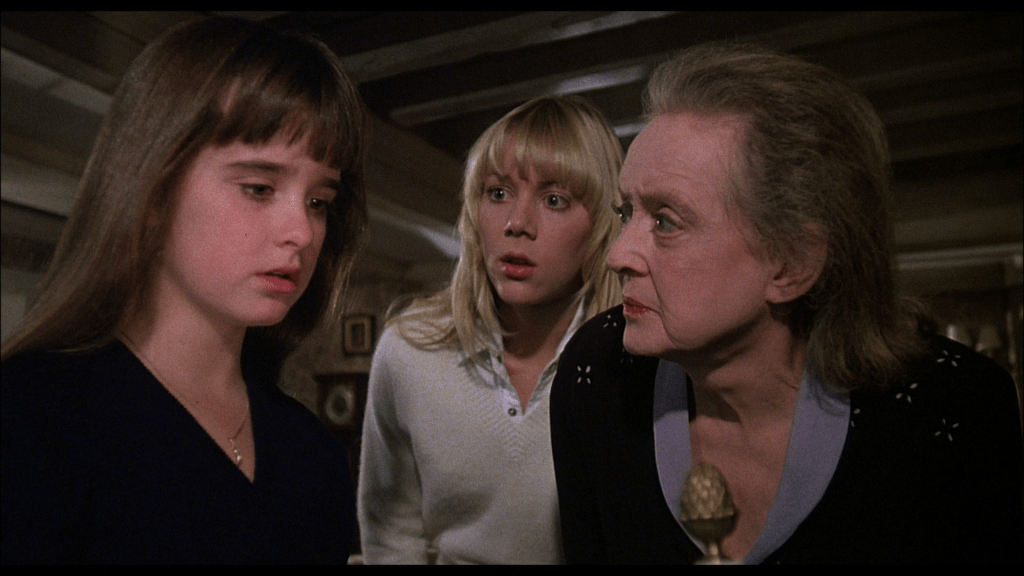

The Curtis’ daughters were played by Kyle Richards and Lynn-Holly Johnson.

Kyle Richards played younger sister Ellie. She was already an experienced juvenile actor at 10 years of age, making her debut in a 1974 episode of Police Woman and subsequently appearing in Little House on the Prairie, Police Story, Eaten Alive, and The Car. In 1978 she had played Lindsey Wallace in John Carpenter’s Halloween – a role she would revisit 43 years later in David Gordon Green’s Halloween Kills (2021).

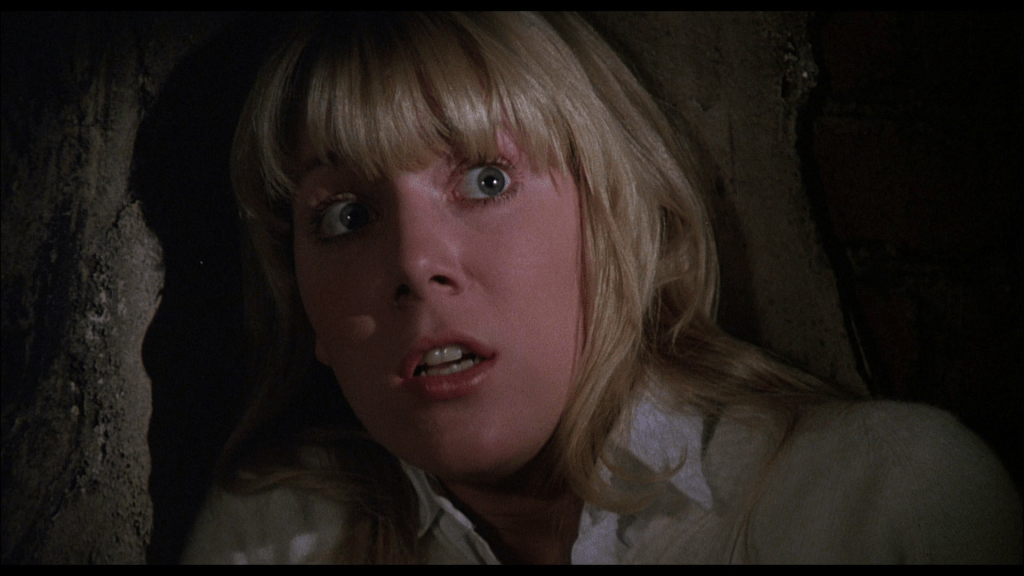

Older sister Jan, who drives much of The Watcher in the Woods’ plot, was played by Lynn-Holly Johnson; not an actor, but a figure skater. She had won a novice silver medal at the 1974 US Figure Skating Championship at the age of 16, but retired from the sport three years later. In 1978 she made her screen debut in the romantic skating drama Ice Castles. The Watcher in the Woods marked her second role. Despite playing much of the film against Bette Davis, Johnson claimed not to be intimidated: ‘I certainly knew who Bette Davis was. And with my background being a competitive figure skater since I was five years old, all I knew was to train hard. Just keep working hard. And Miss Davis really liked me for that reason.’[5]

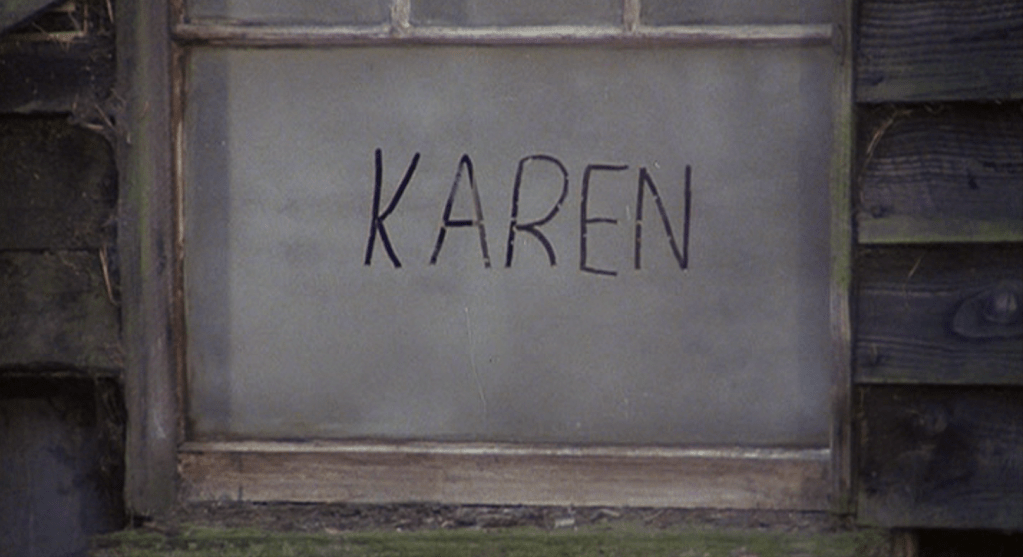

Jan is immediately confronted by supernatural phenomena, including spontaneously breaking windows and mirrors, and flashing lights in the forest. Ellie, meanwhile, is hearing voices and automatic-writing the name “Karen” backwards in a window. It is soon revealed Karen is the name of Mrs Aylwood’s long-missing daughter, and her friends who last saw her alive – now all middle-aged adults – do not appreciate Jan poking around for answers.

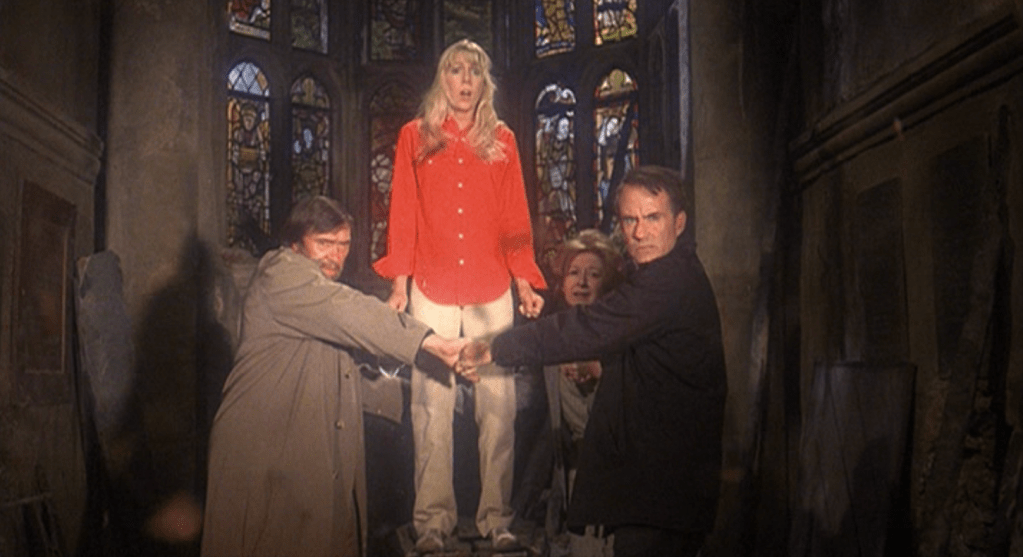

The now-adult friends were played by Ian Bannen, Richard Pasco, and Frances Cuka. Bannen was a noted Scottish actor who would subsequently appear in Disney’s 1983 thriller Night Crossing. Pasco was largely a theatre actor, but who had performed in several Hammer Studios features including The Gorgon (1964) and Rasputin, the Mad Monk (1966). Cuka came from television, although in 1972 she played Catherine of Aragon in Waris Hussein’s film Henry VIII and his Six Wives.

In a key horse-riding scene, Johnson – who had extensive training – was permitted to conduct her own stunts. This choice backfired when she was almost seriously injured while shooting the sequence. ‘The stunt coordinator and the director on the truck,’ said Johnson, ‘kind of forgot I’m this actress and I’m supposed to be spooked. When they said action, I start screaming and the horse hears the screaming, and the horse gets spooked and goes crazy and gallops really fast. The director on the truck is going “Wow, she’s really going — it’s just great.” Of course, the path comes to an end much quicker when you’re going that fast, and the horse put out the front paws straight to stop, and I flipped off the horse and landed in a bunch of leaves.’[6]

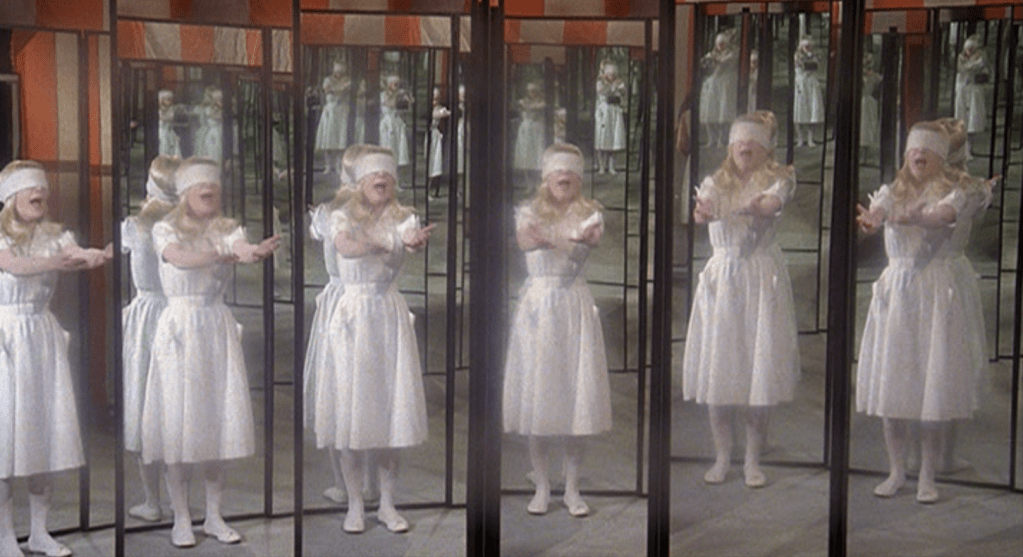

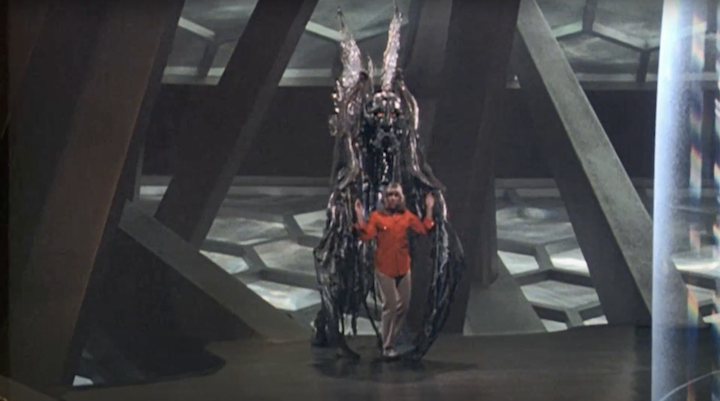

One of the more striking elements of Florence Engel Randall’s novel A Watcher in the Woods was that it transitions during the course of the book from a supernatural story to a science fiction one. The mysterious “watcher” that Jan is attempting to track down is revealed to be an alien child from a world where time passes much more slowly than on Earth. In a traditional ritual gone wrong, the Watcher had swapped places with Karen Aylwood.

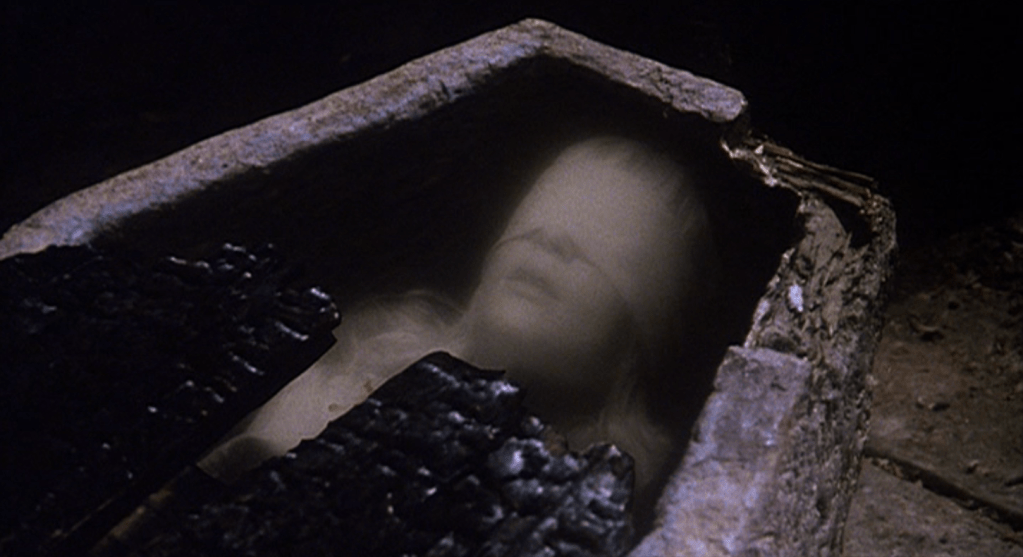

Disney’s adaptation retained the science fiction ending, but instead of revealing the Watcher to be a pretty young girl with a pointed chin – as imagined by Randall – it was re-imagined as an insectoid, bat-like creature with a more horrific and inhuman appearance. The Watcher was designed by Harrison Ellenshaw, a visual effects supervisor who had created numerous matte paintings for Star Wars (1977) and The Empire Strikes Back (1980).

The main production shoot concluded on 2 November 1979 after 12 weeks. The Watcher in the Woods made its premiere on 17 April 1980 at New York’s Ziegfeld Theatre.

The date was selected to coincide with Bette Davis’ 50th anniversary on screen; the film marked her 85th feature. The intention was to run the film exclusively at the Ziegfeld until 7 June, where it would open widely on 6-700 screens across the USA. That intention was not realised. Initial press reviews were brutal. Variety’s review claimed ‘the acting and writing are barely professional’.[7] Other reviews tended to be peppered with terms like ‘ridiculous’[8], ‘dreary’[9], and ‘horrid’[10]. In the New York Times, critic Vincent Canby wrote ‘I challenge even the most indulgent fan to give a coherent translation of what passes for an explanation at the end’.[11] It was the ending that seemed to torpedo Watcher’s chances. ‘Even after they released it,’ Bette Davis later told her biographer, ‘Disney couldn’t decide how to end Watcher in the Woods.’[12]

On 20 May 1980, facing negative reviews and equally poor box office, Walt Disney Productions took the rare step of withdrawing The Watcher in the Woods from release entirely. An official statement claimed the withdrawal was due to ‘certain technical aspects of the film, particularly the ending’.[13] In private, everybody knew the problem was the terrible ending: that the Watcher of the title turned out to be a poorly realised inter-dimensional alien. One anonymous source within Disney claimed that ‘everyone inside, except Ron [Miller], said we shouldn’t show anything of the Watcher. He was trying to show a visible monster kind of thing; an alien being of sorts.’[14]

Ellenshaw, who had developed much of the ending’s visual effects, explained: ‘They had tried to blend science fiction with a ghost story, and it didn’t work. They tried to get a scary alien, but he came out looking like a large lobster with seaweed hanging off him. It was as though the audience had wandered into another picture. You can’t break the rules that late in a movie without having the audience feel someone got the last reel mixed up.’[15]

The plan was to re-edit the film’s unpopular climax and release it back into the market. By the time Disney actively pulled the film from the Ziegfeld Theatre, it had grossed a disastrous US$42,000. Screenings of Fantasia (1940), which replaced Watcher for the final week of its planned engagement, grossed US$50,000.

Test screenings of the revised cut quickly made it clear that simple edits had not helped. While audiences appeared to like the bulk of the film, the climax performed so poorly that they disliked the film overall and would not recommend it to others. In an unprecedented move, Disney allocated an additional million dollars to The Watcher in the Woods’ budget and commissioned an entirely new climax. The wide release of the film was delayed to late 1981; an already planned re-release of 1964 hit Mary Poppins was brought ahead in the schedule to replace existing theatre bookings. ‘’Why did we do it?’ said Tom Leetch. ‘We felt we had seven-eighths of a good picture, but the ending confused people.’[16]

Undertaking reshoots were possible because the sets of the film had been dismantled at Pinewood, but not disposed of. An actor’s strike delayed the reshoots until later in 1980. While this was not a major issue in regards to the adult cast, for young Kyle Richards it was a different matter. Lynn-Holly Johnson said: ‘When we reshot the Watcher’s ending at Pinewood Studios in England, I was already there shooting 007’s For Your Eyes Only. One funny thing I do remember was that when we went to reshoot, Kyle had grown about 6 or 8 inches taller in that year since we had wrapped the film.’[17] The difference in age for both Richards and Johnson is clearly visible in the re-shot climax.

Disney stalwart Vincent McEveety (The Million-Dollar Duck, Herbie Goes Bananas) directed the reshoots as John Hough was already shooting his next feature Incubus in Canada. Only Bette Davis was unavailable; her new scenes were shot separately in Los Angeles at the end of the year. ‘Eventually they tried three different endings,’ she later said. ‘I haven’t the foggiest as to which one they chose for posterity. Not the foggiest.’[18]

On 8 October 1981 The Watcher in the Woods returned to American cinemas, opening on 230 screens with a new edit and a reshot climax. It was hoped that a staggered re-release, moving from regions into major cities like New York and Los Angeles, would build word of mouth and create growing demand.

The gambit took place at the end of a crushing year for Walt Disney Productions in cinemas. Their action comedy Condorman lost the studio almost US$10 million on its own, while the failures of Dragonslayer, Amy, and The Devil and Max Devlin collectively accounted for another US$10 million. Only The Fox and the Hound turned a significant profit, bringing in US$15 million of revenue on its own.

The re-release failed: The Watcher in the Woods grossed roughly USD$5 million, well below its final production budget. 45 years later it sits in relative obscurity, unavailable on either home video or streaming. In 2017 a fresh adaptation of the book was produced for cable network Lifetime, starring Angelica Huston and directed by Melissa Joan Hart. In a nod to the original, actor Benedict Taylor – who played neighbour Mike Fleming in Disney’s film – played Ian Bannen’s old role of John Keller.

It is hard to not to acknowledge The Watcher in the Woods as an unmitigated failure. Its pace is too slow and pedestrian, still resembling a 1960s Disney family film over-and-above anything suitable for an early 1980s audience. While effective supernatural moments succeed in fits and starts, they are too sparsely incorporated and fail to build on one another. While much of the adult cast deliver solid and dependable performances – Davis, McCallum, Bannen, and the like – the film’s focus is on Lynn-Holly Johnson, who is simply not a strong enough actor to support the entire feature.

Ironically the alien creature climax that saw the film pulled from cinemas is the stronger of the two that were released. While there are faults with Ellenshaw’s so-called “lobster with seaweed”, it is at least original and visually interesting. The reshoot ending simply fails to explain anything, and ends the film on an empty, frustratingly empty note.

The Watcher in the Woods is widely credited for being Disney’s first attempt at horror, which is only really true if one only considers the company’s life-action productions. Truth be told, Disney had been dabbling with horror and supernatural themes as far back as their original Silly Symphony “The Skeleton Dance” (1929). Within the first year of the Silly Symphonies commencing, another short – “Hell’s Bells” – was literally set in Hell with a cast of demons. Early features including Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Pinocchio (1940), and Fantasia (1940) all incorporated horror elements. The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr Toad (1949) remains one of the finest expressions of the genre in an animated film, and heavily influenced Tim Burton’s own 1999 horror film Sleepy Hollow.

Not the first, then, and certainly not the last. Just one year later the company would release Something Wicked This Way Comes, based on the Ray Bradbury novel. Return to Oz (1985) was uncharacteristically frightening for a Disney film, while The Black Cauldron (released the same year) marked the first-ever horde of zombies to grace the company. By the end of the 20th century, horror broke out from sections of Disney’s animated output and was fully embraced by live-action again. Hocus Pocus (1993), The 13th Warrior (1999), and Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (2003) brought scary scenes and supernatural creatures to the cinemas to growing commercial success. Subsequent attempts included four Pirates sequels, The Village (2004), and Dark Water (2005).

Pure horror has largely lay outside of Disney’s brand and grasp, but where the studio has always excelled is in horror as a tool: flavouring and highlighting other kinds of films by understanding a family audience can accept and embrace frightening scenes within a generally reassuring context. The Watcher in the Woods, if it is anything, is a demonstration of how difficult fitting full horror into Disney’s identity really is, and how heavily that identity’s gravity will pull any attempt out of shape.

[1] Scott Michael Bosco, “The Watcher in the Woods: The mystery behind the mystery”, Digital Cinema, 5 May 2002.

[2] Quoted in “John Hough: “I am happy to say that Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry is one of Quentin Tarantino’s favorite films””, Film Talk, 30 August 2017.

[3] Graham Greene, “The Cinema”, The Spectator, 19 June 1936.

[4] Quoted in “John Hough: “I am happy to say that Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry is one of Quentin Tarantino’s favorite films””, Film Talk, 30 August 2017.

[5] Mike Pingel, “‘Watcher in the Woods’ Star Lynn-Holly Johnson’s Bette Davis Regrets and ‘Crazy’ On-Set Accident”, Remind, 9 October 2025.

[6] Mike Pingel, “‘Watcher in the Woods’ Star Lynn-Holly Johnson’s Bette Davis Regrets and ‘Crazy’ On-Set Accident”, Remind, 9 October 2025.

[7] Variety staff, “The Watcher in the Woods”, Variety, undated.

[8] Kathleen Carroll, “Guessing who’s the peek-a-boo”, New York Daily News, 19 April 1980.

[9] Gene Shalit, “The Watcher in the Woods review”, Ladies Home Journal, July 1980.

[10] Bonnie Allen, “The Watcher in the Woods”, Essence, July 1980.

[11] Vincent Canby, “The Watcher in the Woods”, New York Times, 17 April 1980.

[12] Charlotte Chandler, The Girl Who Walked Home Alone: Bette Davis A Personal Biography, Simon & Shuster UK, London, 2008.

[13] Andrew Epstein, “The Watcher: All’s well that ends well – almost”, Los Angeles Times, 25 May 1980.

[14] Andrew Epstein, “The Watcher: All’s well that ends well – almost”, Los Angeles Times, 25 May 1980.

[15] Aljean Harmetz, “Watcher in Woods, revised $1 million worth, tries again”, New York Times, 20 October 1981.

[16] Aljean Harmetz, “Watcher in Woods, revised $1 million worth, tries again”, New York Times, 20 October 1981.

[17] Mike Pingel, “‘Watcher in the Woods’ Star Lynn-Holly Johnson’s Bette Davis Regrets and ‘Crazy’ On-Set Accident”, Remind, 9 October 2025.

[18] Charlotte Chandler, The Girl Who Walked Home Alone: Bette Davis A Personal Biography, Simon & Shuster UK, London, 2008.

Leave a comment