Sequels are an inevitable aspect of commercial filmmaking. If the ultimate purpose of a company making a feature film is to earn a profit, and that film is particularly profitable, common sense dictates that another film in the same mode and style is more likely than not to turn a profit as well.

In terms of features, it is broadly acknowledged that Thomas Dixon Jr’s The Fall of a Nation (1916) was Hollywood’s first sequel, following up as it does on D.W. Griffith’s notorious The Birth of a Nation, which was released to great commercial success a year earlier. Decades later the sequel became particularly common among horror movies. This was no great surprise: horror films in general tended to be cheaply made compared to other genres, and generated very healthy profit margins. The explosion of the slasher genre following the release of John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) seemed particularly amenable to sequels, with those franchises following their villains from film to film rather than any kind of hero or protagonist. Halloween itself, between 1978 and 2025, has generated 12 sequels, remakes, and reboots. There has been similar longevity expressed by Friday the 13th (1980, 11 derivative works), A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984, eight follow-ups), and even foreign horror series such as Ring (1998, seven sequels in Japan alone) and The Grudge (seven Japanese follow-ups since the direct-to-video original in 2000).

The perceived wisdom, and – to be honest – a broadly reliable one, is that horror franchises get worse over time. Sequels, which innately lack the originality of the preceding work, tend not be as popular or as well received by critics. There are, of course, exceptions. This leads neatly to Darren Lynn Bousman’s 2007 thriller Saw IV. Not only is comfortably the most effective Saw sequel – at the time of writing the series has seen nine in total – it is in many ways a superior achievement, both narratively and technically, to the 2004 original. It is, in essence, a deeply under-valued sequel wedged halfway through a deeply under-valued and misunderstood franchise.

It is, of course, impossible to expansively discuss the fourth film in a series without at least briefly touching upon the original three. Saw was the creation of aspiring creatives James Wan and Leigh Whannell. They met in Melbourne, Australia – Whannell was born there, while Wan immigrated from Malaysia – and both studied film at local institution RMIT University. Wan wanted to direct professionally, and Whannell to act, and together they developed ideas for a low-budget film concept with which they could break into the industry. Their successful project was Saw (2004), a violent and bloody thriller in which two men wake up chained to opposite walls of an abandoned bathroom with a dead body lying between them. A low-budget 2003 short film sold the concept to American production company Twisted Pictures, and the resulting feature – directed by Wan and written by and co-starring Whannell – was a surprise hit at the Sundance Film Festival and picked up for distribution by Lionsgate Films for wide release.

The commercial success of Saw – USD$104 million worldwide – led to Lionsgate to hurriedly commission a sequel. When Saw II, directed by Darren Lynn Bousman from a script by Bousman and Whannell, grossed a further USD$153 million, a second sequel inevitably followed. Saw III grossed USD$165 million – more than either of the first two films – making yet another instalment inevitable. On a creative level, however, it was a different matter. Keen to work on other films, Whannell and Wan – who had both remained active producers on the series – took a partial step back. Bousman, having directed one Saw sequel after another, assumed the same. When it became clear that the series was continuing he agreed to return for a third and final time.

While promoting Saw IV, Bousman admitted: ‘In Saw III, I thought it was my final one and I said, “Kill everybody! Kill them all!” and I went in and I killed Tobin and I did everything, and now I’m like, alright I’m back, everyone’s dead, what am I gonna do?’[1]

The Tobin that Bousman refers to is actor Tobin Bell, who played serial killer John Kramer, aka “the Jigsaw killer”, across all three films to that point.

Kramer is barely seen in the original Saw. He is later revealed to be a successful architect who, upon receiving a terminal cancer diagnosis, makes a failed suicide bid and emerges with a renewed appreciation of life. He then engages in a series of kidnappings, trapping his victims inside elaborate contraptions that require them to shed significant amounts of blood or body parts to survive. By fighting to survive, so Jigsaw’s theory goes, one will emerge with a proper appreciation of their life and what they have. In practice these victims generally die horribly, unable to achieve the tasks that their captor has set.

The first film focused on oncologist Dr Lawrence Gordon (Cary Elwes) and photographer Adam (Whannell). In the second film, Kramer appears to be caught during the film’s first act, but an elaborate gambit sees him not only escaping custody but abducting the very police officer who appeared to catch him: the corrupt Detective Eric Matthews (Donnie Wahlberg). The third film saw a bed-ridden Kramer betrayed by his apprentice and apparently killed along with her.

As Bousman noted above: everyone relevant to the franchise’s future appeared to be dead. Lionsgate and Twisted Pictures were keen to continue profiting from the concept, but how does one continue?

It is worth noting this was hardly a problem unique to Saw. It is glaringly obvious to the casual observer that Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare was the sixth of nine films, and that Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter was fourth in its series; Jason Goes to Hell: The Final Friday was ninth. The problem that was relatively new for Saw related to genre: other horror franchises embraced supernatural themes and fantasy to regenerate their antagonists, while Saw had been resolutely based in a realistic, non-fantastical universe. There would be no scenes of Kramer crawling back from the grave.

One option explored by Twisted Pictures was a prequel, showing how John Kramer originally became the Jigsaw killer. A speculative screenplay was even identified: The Midnight Man by Patrick Melton and Marcus Dunstan, which portrayed a situation that could, with rewrites, inspire the younger Kramer to become a killer. Producers Oren Koules and Mark Burg were not convinced by the prequel approach. Melton recalled: ‘Well, the story is that Leigh didn’t want to do any more after 3. So, they were looking for writers. They didn’t have much of a story for 4, and an executive over at Twisted read The Midnight Man and thought it could be a good prequel, explaining a traumatic incident that happened to John Kramer when young. Mark and Oren didn’t want to do a prequel like that, so the idea got squashed, but the script as a sample is what got us the deal to write Saw 4, 5, and 6.’[2]

Knowing that they could be writing up to three Saw pictures enabled Melton and Dunstan to conceive of the new sequel as the first part of a loose trilogy, revealing that Kramer had a second apprentice and then following that new killer’s journey to fully replace him. The idea of fleshing out Kramer’s own back story still had its appeal, however, and would mean the film could continue to use the popular Tobin Bell in the role. In the end, the core plot of Saw IV would focus on establishing a new lead while showcasing Kramer’s past through flashbacks.

It is a smart structure, and delivers a complexity to the finished film that the other Saw instalments quite honestly lack. It also effectively makes Saw IV – in structure if not in quality – the Godfather Part II of franchise horror movies.

For a film intended to give the Saw series a fresh longevity, Saw IV is remarkably reliant on the previous three parts. The central role is handed to SWAT commander Daniel Rigg, played by Lyriq Bent. The character had appeared in a supporting capacity in Saw II and III, and the shift to centre stage afforded the series a new focus with a sense of familiarity. Other returning actors included Costas Mandylor and Dina Meyer as police detectives Mark Hoffman and Allison Kerry, Betsy Russell as Kramer’s widow Jill Tuck, and Donnie Wahlberg as Eric Matthews. In one interview Mandylor remarked ‘the beauty of the Saw movies – or maybe the tragedy? – is that if you live through one you’re probably going to be in the next one.’[3]

By 2007, the Saw films had slipped into a familiar but somewhat rushed production routine. The production office opened in Toronto on 12 February, with shooting taking place over six weeks from April. Post-production would then continue up to the film’s release in late October. Saw IV was assigned a production budget of USD$10 million, roughly in line with Saw III.

The rapid production schedule regularly challenged the franchise’s crew. ‘It has been a challenge not only to provide believable visual effects,’ said effects supervisor Jon Campfens, ‘but to do them in a compressed time frame. Each new Saw film is approved after the previous release and success. So, we have less than one year to write, staff, shoot and post each succeeding film.’[4]

The originally contracted director of Saw IV was David Hackl, who had worked as production designer on the previous two sequels. When his wife was diagnosed with cancer (she later recovered), Hackl withdrew from the position. With production about to commence, Twisted Pictures’ producers convinced Darren Lynn Bousman to come back and direct for a third time.

While it is worth running through the narrative of Saw IV to appreciate both how it was made and the cleverness of its screenplay, such a process will inevitably reveal its surprises and plot twists. As a result, any reader that has not seen the film but plans to should probably do so now and return to this essay later.

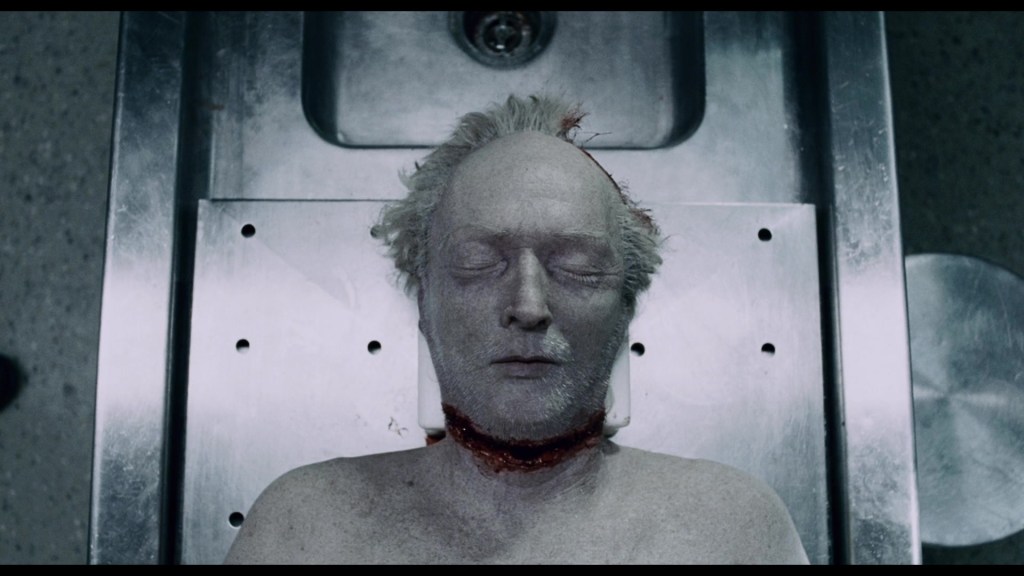

The film begins with the autopsy of James Kramer. The scene is rendered in graphic detail; in fact, if it was not for its clinical nature it would easily stand as the goriest sequence of the entire Saw franchise. It is a hugely effective way to begin the film, since it emphasises the conclusion of the previous one and removes all doubt in the mind’s audience. The Jigsaw killer is dead, and to guarantee that is the case the audience sees his chest spread open and his brain removed from his skull. When an examination of Kramer’s stomach reveals a wax-coated micro-cassette, the coroner immediately calls police detective Mark Hoffman. Hoffman plays the tape right there in the morgue, and listens to Kramer’s voice assure him that his murderous work will continue from beyond the grave.

The film immediately jumps to its first ‘trap’ sequence: two men wake in a mausoleum, both chained by the next to a large mechanical device. The device activates, rolling up the chain of each victim until they will be killed by it. The key to each man’s shackle is clearly attached to the neck of the other, but someone has sewn shut one man’s eyes and the other’s mouth. Unable to see, the eyeless man impulsively struggles to attack the mouthless one, who is unable to communicate. After a brief struggle the mouthless man murders his companion, retrieves the key, and frees himself – his lips splitting from the thread as he screams in pain.

This seems an appropriate point at which to discuss Saw’s traps, which are an integral element of the franchise and almost certainly the one which attracted the most public attention. They are also the most contentious part, aligning Saw with the popular ‘torture porn’ movement of extreme horror during the early 2000s.

To understand Saw’s relevance to post-millennial extreme horror, and more importantly to explain how it differs from it, it is worth considering another popular example of the genre at the time. Eli Roth’s film Hostel (2005) featured a group of over-sexed American backpacker who, while travelling through Eastern Europe, are kidnapped and trapped inside an elaborate maze of torture chambers where rich dilletantes pay lavish sums to cut up, evicerate, and otherwise dismember innocent people. The horror of the film stems not from suspense but from disgust, and audiences can vicariously experience this particular sort of revulsion in a cathartic fashion.

The traps in Saw generally differ from the Hostel model, in that its victims are placed inside some kind of apparatus or situation and then driven to either do nothing and die or take action, deliberately hurt or disfigure themselves, and potentially survive. The victims are typically people that have done bad things, or who – in Jigsaw’s eyes – failed to sufficiently appreciate their own lives. The scenes inspire the same sense of disgust or shock that Roth’s film inspires, but it adds additional layers of moral quandary and speculation. Does the viewer have the same reaction to seeing a guilty person tortured as an innocent one? Would each viewer, if they found themselves in the situation depicted on-screen, be able to take the same desperate measures? It is this additional complexity that pushes Saw not to a ‘higher’ level than most of its contemporaries, but certainly to a more complex and interesting one.

While promoting the film Tobin Bell said: ‘Groups of skateboarders come up to me and start to talk to me about the Saw movies. And generally, they talk a lot about the concepts that are in the films. I’m always interested in that. They don’t talk that much about the traps.’[5]

Bousman said ‘Take away the scenes of blood and you still have the movie, where a lot of the horror films you take away the scenes of blood and there’s nothing left. And I think that’s what the Saw films have done so well. Remove every trap in the movie and you’ll still have the movie there.’[6]

Both Saw’s elaborate torture mechanisms and the broader extreme horror films exist as modern interpretations of much older story genres – they are, in effect, little different from the grand guignol theatre of 19th century France. They also come from a tradition of cultural entertainment responding to trauma. Just like the Marquis de Sade wrote his controversial fiction in the shadow of the French Revolution, or Godzilla and Astroboy came to being following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, so Hostel, Saw, and a raft of other American films came to fruition in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks of 2001. It is cinema as a reflex action: art reflecting back to a mainstream audience, and screaming ‘everything is fucked’ at the top of its lungs to anyone needing to listen.

Some years later, while promoting his 2021 Saw sequel Spiral, Bousman admitted ‘the whole trap part is such an arduously dense, not fun process. When we get the script it’ll have a slug where it might say “Guy dies in a tunnel. Trap to come.” We then have to find out through pre-production what that is, and it’s a process. It’s got to reflect the narrative, the theme, the character… and it also has to be something we haven’t done before, and that’s hard.’[7]

Patrick Melton said ‘eventually we’ll have to write out very specific traps. It’s totally analytical at this point: What have we done before and what can we do now? What’s the theme?’[8] Marcus Dunstan added: ‘The genesis of these traps can sometimes just come from, “Alright, we’re going to punish the idea of lying today. What can we take from a liar?” So it’s always based on a sin, a moral flaw where we can figure out the most ironic way to take that away.’[9]

On most Saw films, including Saw IV, the primary responsibility for designing and constructing the traps – and ensuring their safety – lay with David Hackl.

The film’s second trap unexpectedly takes out returning character Allison Kerry, which does have the benefit of raising the suspense for the audience – if one character can be eliminated so suddenly, how safe are the others?

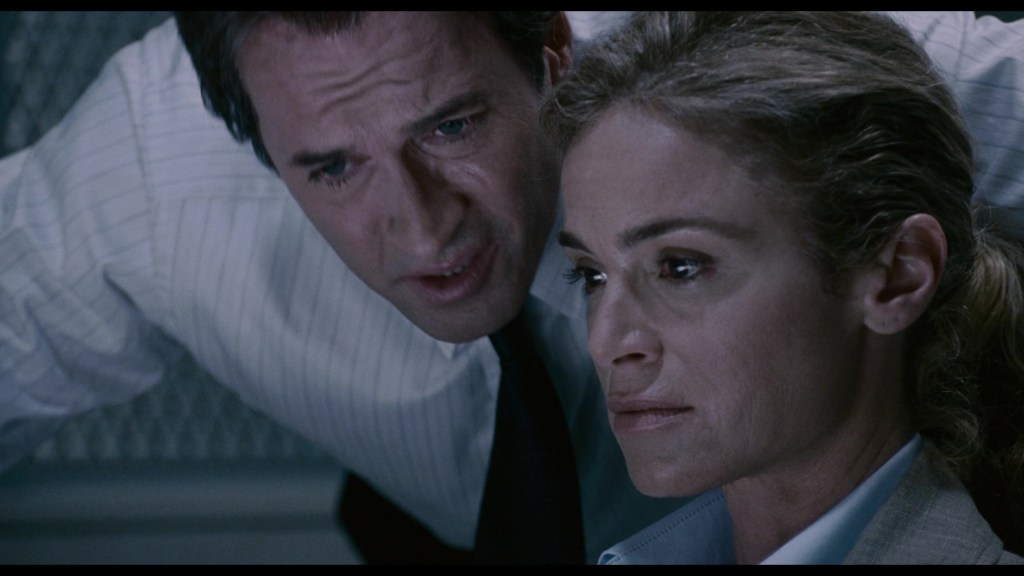

The aftermath of her death serves to introduce the film’s other key protagonists. Rigg is admonished by Hoffman for barging into the crime scene without securing it first, and FBI agents Peter Strahm (Scott Patterson) and Lindsey Perez (Athena Karkanis) introduce themselves and signify that the scope of the Jigsaw investigation has expanded. It is Strahm that deduces there had to be a second accomplice aiding Jigsaw, given the physical labour required to carry and set up Kerry’s body.

That night, both Rigg and Hoffman are abducted. Rigg wakes in his own apartment, where a Jigsaw recording reveals that the long-missing Detective Eric Matthews is still alive. Rigg is given 90 minutes to undertake a series of tests that will educate him about Jigsaw’s methods. The first, a sex trafficker named Brenda, is already trapped inside a scalping machine in the next room. Rigg is warned not to interfere with her test. When he ignores the warning and frees her, Brenda attempts to stab him with a knife. It emerges that she was told Rigg was coming to arrest her.

While the scalping machine was a physical prop, CGI was used to realise the confronting sight of Brenda’s skin ripping from her skull.

This scene includes one of several inventive transitions in the film. Rigg struggles with Brenda, they smash into a mirror, and the camera literally tracks through the mirror and into the police precinct for the next scene. It is not an edit: both sets were constructed adjacent to each other and the location, scene, and cast are changed over in-shot. It is a tremendous achievement in upping the kinetic energy of the film; many viewers do not even notice how the effect was achieved.

A different emotional effect is achieved later on by similar means. A flashback on Kramer ends with the character looking out of frame, and the camera then pivots to look through a one-way mirror to Strahm interrogating Jill Tuck in a present-day interrogation room. It is not just a visually cool transition; it gives the sense of Kramer being present in the room even after his apparent death.

Strahm’s interrogation of Jill enables the film’s key flashbacks, which flesh out John Kramer’s back story and explain the process by which he became the Jigsaw killer. Earlier films had explained how a terminal cancer diagnosis was instrumental. Saw IV adds the personal tragedy of Jill miscarrying their unborn child after an altercation with the drug addict Cecil (Billy Otis). Cecil later becomes Kramer’s first victim.

The Saw films undergo a strange transition in how they treat Kramer’s character. In the first film he is a nameless and faceless antagonist; more plot function than character. Saws II and III humanise him to an extent, giving him an albeit twisted moral purpose and an actual personality with which the audience may connect. From here, the films under Melton and Dunstan actively attempt to garner sympathy for him. It contrasts him over the following films with his apprentices, who are developed in more monstrous ways. Actor Scott Patterson said: ‘I think that’s what makes this movie special and different from all the other Saw films. You’re taking a man that is capable of doing this and you’re seeing another side of him.’[10]

Some impressive work is undertaken during this flashback sequence to link Saw IV back into the previous films of the franchise. Three patients in Jill’s clinic are future Jigsaw victims (Paul and Donnie from Saw, Gus from Saw II). While waiting outside in his car, Kramer is propositioned by Addison (Emmanuelle Vaugier) from Saw II. The nurse who initially treats Jill’s miscarriage is seen near the beginning of Saw III, arguing with that film’s protagonist Lynn. While there has been connective tissue linking the previous films together, Saw IV really marks a shift into an active attempt to interweave them all together.

The main thrust of the story follows Rigg from test to test: first to a seedy motel, where the manager is revealed to be a serial rapist, and then to an abandoned high school, where an abusive husband and his victim wife have been impaled together by metal rods. The spikes impaled in the couple’s bodies were once again achieved through a combination of practical effects and computer-generated images (CGI). 175 CGI-enhanced shots were incorporated into the film overall, the most to date for a Saw film.

Hot on Rigg’s tail, Strahm and Perez learn that all of the new Jigsaw victims were previously defended by lawyer Art Blank (Louis Ferreira), who also represents Jill Tuck. In a flashback, he is revealed to be the victim with his lips sewn together at the beginning of the film. He now monitors another trap while attached to an apparatus that threatens to ram a spike into his neck if he does not comply. The trap he monitors threatens to crush Eric Matthews’ skull between two ice blocks and electrocute Mark Hoffman if activated.

At the time of Saw IV’s writing Wahlberg was unavailable for the shoot due to other acting commitments. As a result his role as the victim of the film’s ice trap was rewritten to incorporate Rigg’s wife Tracy. When Wahlberg later became available, the production reverted to the original plan. Tracy (played by Ingrid Hart) barely appears in the finished film.

In the film’s climax, Rigg and Strahm’s journeys converge at the same abandoned factory site. Rigg is confronted with a sealed door, and is once again admonished to hold back and not interfere. With his 90-minute deadline almost expired, he breaks open the door – only to be shot by Matthews in an attempt to keep him away. His test is revealed to be the opposite of what he assumed: the solution was not to beat the deadline but to let it pass. His misplaced sense of urgency activates the trap, killing Matthews, Hoffman, and Blank at the same time. A stunt artist stood in for Donnie Wahlberg as Matthew’s body collapsed onto the floor. The artist’s head was obscured by a green hood on set, and was replaced during post-production by a gory multi-layered model created with the 3D software package Maya.

This is a typical climax for a Saw feature, and is immediately reminiscent of the ends of the second and third films – where characters essentially lose because they failed to follow instructions. One would easily be forgiven in the moment for assuming the film ends there.

Strahm, however, has taken a different route through the factory. He finds himself in another room, and walks directly into the shooting death of Jigsaw co-conspirator Amanda Young (Shawnee Smith), and Jigsaw’s murder at the hands of Saw III protagonist Jeff Denlon (Angus Macfadyen). Jeff turns his gun on Strahm, and Strahm shoots him out of instinct.

In a moment, the entire narrative order of Saw IV is up-ended. It is revealed to not be a sequel to Saw III at all; instead, events have been occurring simultaneously with the previous film. The two climaxes dovetail together.

A dying Rigg sees the presumed-dead Hoffman rise from his trap. He is revealed to be the second Jigsaw accomplice. He leaves Rigg to die, seals Strahm inside his room, and escapes from the scene. The film’s final scene is also its first: Hoffman attends Kramer’s autopsy, recovers the cassette, and hears his master’s message. The killings will continue because Hoffman will take over as Jigsaw.

The previous Saw films were composed of traps, and each ended on a narrative twist. In Saw IV it is the entire film that is, in effect, the trap. Bousman again: ‘I think the Saw films have become kind of known for their twists and “did we get you”. And this entire movie is a lead up to “did we get you”.[11]

Nobody is likely to offer up Saw IV as an example of the highest quality filmmaking. It was produced on a tight budget and a short production schedule, embracing its garish displays of blood and violence to appeal to a specific audience. Like many horror films, it was not embraced by the critics. There are better examples of cinema out there by effectively every measure.

What I would offer up, however, is that Saw IV excels by one very specific criterion: it is undoubtedly one of the best and most effective sequels ever produced. It takes a well-developed and familiar formula, and innovates wildly. It plays unexpected technical and narrative tricks. It gives its target audience exactly the sort of content they expect, but then it ups the ante wildly and gives them an even more twisted, labyrinthine example of the form. More significantly, as a sequel Saw IV cannot exist, function, or succeed on its own merits. It is not simply a sequel because it followed an earlier movie. It is a sequel because it has to be, and takes every advantage of its position.

At the time of writing there have been six more Saw sequels produced, none of which have come close to exploiting their context as well as Saw IV does. I am not sure any sequel has.

[1] Stax, “Interviews: Saw IV Cast & Crew”, IGN, 25 October 2007.

[2] Brad Miska, “How The Collector was almost a prequel to Saw”, Bloody Disgusting, 13 July 2009.

[3] Rawshark, “Interview with Costas Mandylor from Saw IV”, Eat my Brains, 25 October 2007.

[4] Annemarie Moody, “Switching on the gore for the Saw franchise”, Animation World Network, 4 November 2008.

[5] B. Alan Orange, “Tobin Bell’s first interview since completing Saw IV”, Movieweb, 13 June 2007.

[6] Stax, “Interviews: Saw IV Cast & Crew”, IGN, 25 October 2007.

[7] Peter Grey, “Interview: Spiral director Darren Lynn Bousman on returning to the Saw franchise”, The AU Review, 13 May 2021.

[8] Christopher Monfette, “The anatomy of a trap”, IGN, 30 October 2009.

[9] Christopher Monfette, “The anatomy of a trap”, IGN, 30 October 2009.

[10] Stax, “Interviews: Saw IV Cast & Crew”, IGN, 25 October 2007.

[11] Stax, “Interviews: Saw IV Cast & Crew”, IGN, 25 October 2007.

Leave a comment