‘Nothing went like it was supposed to on this movie. Literally. Everything fucked up.’[1]

The movie in question is Panic Room, a 2002 thriller starring Jodie Foster and Forest Whitaker, and that frank assessment is from its director David Fincher. If you watch the film, the sort of chaos Fincher describes seems almost unbelievable. It is set almost entirely inside a New York brownstone mansion. Three men break inside to steal the contents of a hidden safe. The residents – a mother and her daughter – take shelter inside the building’s highly secure ‘panic room’. The complication? The safe the burglars are targeting is located inside that same panic room.

The film stands in stark contrast, even today, from David Fincher’s other films. From Alien3 and Seven to Zodiac, The Social Network, and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, Fincher has forged a career typified by complex stories with large casts and extensive visual spectacle. Panic Room seems a genuine outlier among his body of work. Certainly among his films it seems the least discussed and studied. Even the director himself seems unwilling to consider it on a level with his better-celebrated efforts. In one promotional interview he said: ‘I didn’t look at Panic Room and think: Wow, this is gonna set the world on fire. These are footnote movies, guilty pleasure movies. Thrillers. Woman-trapped-in-a-house movies. They’re not particularly important.’[2]

Personally I think he underrates both the genre and his work inside it. Panic Room is a beautifully performed, inventively shot commercial thriller that uses a narrow physical setting to ratchet up tension and a smartly written screenplay to give the characters an uncharacteristic level of depth and complexity.

Of course, if one dives behind the scenes to learn about how it was made and the challenges faced by its production team, then yes: nothing went like it was supposed to on this movie.

Everything fucked up.

‘I definitely felt after Fight Club that I had just spent two years of my life waiting for trucks to be unloaded,’ said Fincher.[3]

By 2000, the 38-year-old David Fincher had worked as a visual effects worker, then as a director for commercials and music videos. In 1992 he made his feature directing debut with Alien3, the production of which was so fraught with studio interference that he has since effectively disowned it. Seven (1995) was much more successful, and was followed by the labyrinthine thriller The Game (1997) and most recently by the wildly ambitious literary adaptation Fight Club (1999). That film had been envisaged by its producers as a relatively modest production costing USD$23 million; under Fincher’s direction it cost an estimated USD$65 million with extensive digital and visual effects, 300 scenes shot, 200 filming locations, and over 1,500 rolls of film.

Fincher said: ‘My agent sent me this script and said, “You’re not going to want to read this because it all takes place in one house, and it’s a logistical nightmare,” and I was just, “I might be interested in that!” I’m a little bit of a contrarian.’[4]

‘Rear Window is one of my favorite cinematic experiences,’ he later explained, ‘because of the rigors of limitation. I thought something like that would be kind of cool to do.’[5]

The limited scale and locations of Panic Room must have promised an easier ride for Fincher, who nonetheless overlooked the single greatest element that had made his earlier films so complicated to produce. He failed to remember his own creative instincts and ambitions. ‘I kind of like challenges,’ he said, ‘and then you end up two years into the challenge that you’ve made for yourself and you just go “Nothing’s worth this.”’[6]

Panic Room is not a simple home invasion thriller. It is a home invasion thriller that is packed with ambitious long tracking takes and meticulously staged lighting states. Using computer-generated imagery, Fincher’s camera moves seamlessly from room to room, into air vents and door locks, and through the handle of a kitchen’s coffee percolator. It is, with little argument, one of the most complicated visual tellings of a straightforward story in the history of narrative film.

Panic Room was written by David Koepp. ‘This film is short,’ reads the first page. ‘This film is fast.’[7]

The Wisconsin-born screenwriter made his debut with Apartment Zero (co-written with director Martin Donovan in 1988). After co-writing a number of films including Bad Influence, Why Me? (both 1990), and Toy Soldiers (1991), Koepp re-teamed with Donovan to write the screenplay for Robert Zemeckis’ 1992 hit Death Becomes Her. From there he became one of Hollywood’s most in-demand writers, penning screenplays for Jurassic Park, Carlito’s Way (both 1993), The Paper, The Shadow (both 1994), Mission: Impossible (1996), The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997), and Stir of Echoes (1999 – which he also directed).

In 2000 Koepp grew fascinated with a news report about panic rooms: secret secure chambers built into the homes of the world’s mega-wealthy to protect them in the event of a home invasion. He wrote the screenplay ‘on spec’; that is, independently without a backing studio or commercial contract. When his agent put the script up for sale, Columbia Pictures purchased it following a fierce bidding war for USD$4 million.

Koepp explained his goal with the screenplay: that ‘it would take place entirely in the house, there was no going outside the house, and it would only have little dialogue. I succeeded to varying degrees. We did go outside the house at David Fincher’s insistence for the first five pages or so, and there is more dialogue than I had wanted, but you know, the world is too big.’[8]

‘To me, it’s about divorce,’ said Fincher. ‘It’s a movie about the destruction of the home and how far you’re willing to go to hold on to what you have.’[9]

The film focuses on Meg Altman, who has recently separated from her philandering husband – and who buys a new home in New York for herself and her 11-year-old daughter Sarah. She settles on a lavish four-story brownstone building that comes complete with a personal elevator and a panic room attached to the main bedroom. On their first night in their new home, Meg and Sarah are the victims of a violent home invasion by a trio of masked thieves.

There is a palpable contrast between Meg – a seemingly quiet and reserved woman – and the outré nature of the outlandish townhouse she purchases. Koepp said: ‘She’s repelled by it. She’s on a tilt, with her marriage ending, and she overreacts. Why did she choose such an unsuitable place for her? Panic, the clouded judgment in panic.’[10]

I think there is also a degree of spite in Meg’s choice. The film makes it clear that Meg’s husband has cheated on her, and now lives with his new girlfriend. When he eventually appears in the film he is visibly older than Meg. There is a strong sense of Meg having been the attractive younger wife of a rich older husband, now flush with alimony. Does she spend so lavishly on the house simply because she can, or because it feels like spending his money?

Nicole Kidman was originally cast as Meg, with 12-year-old Hayden Panettiere cast as Sarah. Neither actor would appear in the finished film. The Hawaii-born Australian Kidman was seemingly at the peak of a career run in Hollywood, aggressively followed by the entertainment press due to her marriage to film star Tom Cruise, and having co-starring in a string of high profile features including Far and Away (1992), To Die For, Batman Forever (both 1995), Eyes Wide Shut (1999), and Moulin Rouge! (2001). Panettiere had kickstarted her career on the daytime soap operas One Life to Live and Guiding Light, and had performed in A Bug’s Life (1998) and Remember the Titans (2000).

When the house is invaded, it is by three burglars – each with their own distinct identity and motivation. They are led by “Junior”, the arrogant and well-monied relative of the man who previously owned Meg’s townhouse. He is set to inherit a portion of the estate already, but leads the break-in to seize some secret financial asset for himself. Junior was played by Jared Leto, who had worked with Fincher on Fight Club and gained strong notices for performances in American Psycho and Requiem for a Dream (both 2000). ‘Pretentious,’ he claimed, when asked in an interview to describe his character, ‘annoying – you might want to punch him in the face a few times.’[11]

Lured into the scheme by Junior is Burnham, a working class technician who installs panic rooms for a living. The role was played by Forest Whitaker, a widely acclaimed actor following roles in Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982), Good Morning Vietnam (1987), Bird (1988), The Crying Game (1992), and Ghost Dog (1999). Whitaker described Burnham to Black Film: ‘Here’s a guy who goes into a situation he thinks will be very simple. He’s trying to change his life. He has the key to the apartment. He knows the entire layout of the place. But there are people inside and he has to get over that hurdle. Then another accomplice comes into the mix, and that’s another hurdle he has to cross.’[12]

‘The fact that he’s conflicted was really attractive to me,’ said Whitaker. ‘It was really interesting to play. He’s a guy who doesn’t really want to cause any problems; he just wants to take care of himself and his family, and he just keeps getting sucked in deeper and deeper.’[13]

An interloper to the burglary is “Raoul”, a masked man invited by Junior without Burnham’s knowledge. Unpredictable and uncontrollable, Raoul’s volatility and impatience throws Burnham’s carefully developed plans out of control. Fincher cast singer-songwriter Dwight Yoakam, based on his performance in Billy Bob Thornton’s 1996 drama Sling Blade.

With the lead cast assembled, Fincher led a series of read-throughs and rehearsals in the lead-up to shooting.

At first Fincher considered trying to shoot the film in near-total darkness, however this rapidly proved unfeasible. Plans to stage the film on location in an actual brownstone house were also abandoned when it became clear no real building could accommodate Fincher’s planned CGI-enhanced tracking shots. 110 technicians spend a total of 15 weeks assembling the sets to simulate the four-story townhouse. More than 136 tonnes of steel and half a million linear metres of lumber were used, at a total cost of USD$6 million.

Two weeks before the shoot Hayden Panettiere withdrew from the film. She was replaced by 10-year-old Kristen Stewart, whose film debut The Safety of Objects was yet to be released.

At the time of writing Kristen Stewart is a widely acclaimed and award-winning actor, having reached stardom via the popular Twilight teen film franchise and subsequently appeared in the films On the Road (2012), Clouds of Sils Maria (2014), Personal Shopper (2016), and Seberg (2019). At the time of shooting Panic Room in January 2001, Stewart was unknown, inexperienced, and vulnerable. Nicole Kidman – a former child performer herself – immediately took Stewart under her wing to guide her through the production process. In subsequent years Stewart has openly praised the comfort she felt working with Kidman during Panic Room’s first few weeks.

What was envisaged as a simple, controlled shoot rapidly grew more complicated. The panic room itself was a set containing a series of security monitors, linked to cameras installed all around the house. Every scene inside the panic room would require an additional scene shot for each monitor, showcasing the burglars’ activity outside. ‘It’s deceptive,’ said Fincher, ‘because you read a script and it reads like, these guys are doing things downstairs and it’s being seen on video monitors then you cut to the room where two people are trapped and they start talking.’

‘A lot of times when you think it’s really simple you realize that you don’t have enough footage to play on those monitors while the two actors talk so you have to cover that stuff now. What was one setup now becomes three setups.’[14]

Two weeks into shooting, Fincher’s cinematographer Darius Khondji quit the film. In an effort to plot the camera movements in advance, Fincher had pre-visualised the entire film using 3D design software, which not only dictated camera movements but also helped establish the elaborate CGI-enhanced shots he intended to include. In Panic Room, the ‘camera’ would be a constantly moving, seemingly impossible point of view for the audience. Shots would do impossible things. The camera would seem to glide seamlessly through the handle of a coffee pot. It would move through walls from room to room. In one striking moment it would ever follow a key into a lock.

This strictly defined visual plan to the film frustrated Khondji, as did disagreements with Fincher over how to light the sets. In the end he became so dissatisfied that he walked from the shoot. ‘Darius is not a light-meter jockey,’ explained Fincher. ‘He wants to be part of the decision-making process. This movie did not allow that, and it was incredibly frustrating for him.’[15] In Khondji’s absence, Fincher promoted camera operator Conrad W. Hall. It marked Hall’s debut as cinematographer.

Production was thrown into crisis again just days later. While running up a flight of stairs, Nicole Kidman immediately started limping. While the initial assumption was some form of sprain, a precautionary x-ray revealed a hairline fracture beneath the knee: the recurrence of an injury sustained while filming Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge (2001). Continuing to perform in the film was impossible, leaving Columbia Pictures with a difficult choice. Cancelling the production outright would activate an immediate insurance pay-out, but leave a hole in the studio’s release schedule. Suspending production to recast the role of Meg could, by Fincher’s estimate, lead to cost overruns of as much as USD$10 million.

The studio pursued the latter course. A regretful Kidman was released from her contract, and David Fincher was forced to seek a new lead actor at short notice.

In a roundtable interview in 2024, Kidman added that ‘I was in a really bad way. I was like, “I’m having a breakdown.”’[16] The commencement of filming on Panic Room had coincided with Kidman’s widely reported separation from husband Tom Cruise, and also came after a particularly busy run of work including the films Eyes Wide Shut (1999), Moulin Rouge!, The Others, and Birthday Girl (all 2001).

When casting for his 1997 thriller The Game, David Fincher had approached actor Jodie Foster about playing a key supporting role in the film as the daughter of Michael Douglas’ protagonist Nicholas Van Orton. Foster had liked the script and Fincher personally, and initially agreed to play the role. When the script was developed further, and Foster’s role was changed from daughter to sister at Douglas’ request, things became less certain. With Foster’s commitments to Robert Zemeckis’ Contact also playing a factor, she found herself dropped from the film. Foster subsequently sued Polygram Films, claiming they had an oral agreement to star in the film; the claim was privately settled in October 1996.

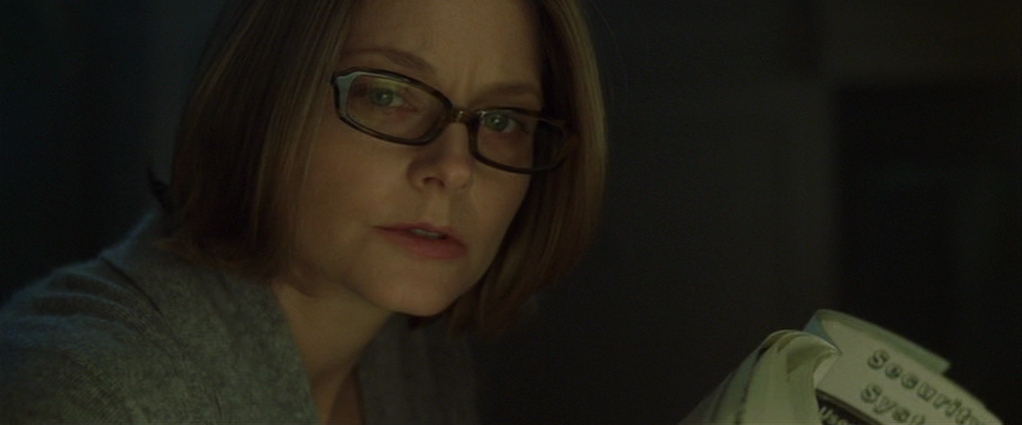

Jodie Foster was – and remains – one of the most talented and acclaimed female actors of American cinema. She started her career as a child model at the age of three. She made her television debut at eight years old, and her film debut at ten. During the 1970s she was a repeat fixture in Walt Disney family films like Freaky Friday (1976) and Candleshoe (1977). She balanced them with surprisingly adult fare in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976, playing a child sex worker) and Nicolas Gessner’s The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane (also 1976, playing a girl menaced by Martin Sheen as a paedophile). Foster won her first acting Oscar for The Accused (1988); she won her second for The Silence of the Lambs (1991) three years later.

Jump forward to early 2001. Foster was actively working to get the film Flora Plum – her third as director – into production. The 1940s-set circus drama was to star Claire Danes and Russell Crowe, but when Crowe injured himself training for the film production was unavoidably delayed. This delay resulted in Foster being unexpectedly available at the exact same time David Fincher was looking to replace Nicole Kidman.

The presence of Jodie Foster in Panic Room irrevocably transformed the film, and it is fairly easy to judge that the transformation was for the better. David Koepp’s original screenplay presents Meg as a deeply vulnerable figure, afflicted with a crippling claustrophobia that complicates her hiding inside the panic room during the film. While this version of the character suited Nicole Kidman’s performance style and physicality, it seemed less appropriate for Jodie Foster. Working with both Foster and Fincher, Koepp rapidly redeveloped elements of his script to make Meg a more resolute and resourceful character. It is entirely to Panic Room’s benefit.

Replacing Kidman with Foster also transforms the relationship between Meg and her daughter Sarah. Foster and Stewart visibly look more like mother and daughter, and share a genuinely strong and realistic rapport on screen. Of course, Foster was another former child actor; Stewart continued to be supported and nurtured during the shoot.

Nine days after accepting the role of Meg, Jodie Foster was on-set and filming. Fincher must have assumed his worst challenges were behind him.

David Fincher did not enjoy the results of his pre-visualisation process. ‘It just felt wrong, like I didn’t get the most out of the actors, because I was so rigid in my thinking,” he said. “I was kind of impatiently waiting for everybody to get where I’d already been a year and a half ago.’[17] In some cases, the pre-visualisation movements were transferred straight from the computer to motion-controlled cameras. While under computer-control, shots could be recorded over and over in exactly the same way, eliminating one variable while Fincher concentrated on other elements.

Technical challenges emerged when Fincher’s pre-visualisations – meticulously calculated down to the centimetre – had to be adjusted for almost every shot of its lead character. When developed during pre-production, they were calculated using the 5 foot 11 inch tall Kidman for reference. When Foster – at 5 foot 3 inches – stepped in, every shot of the film’s protagonist was a full eight inches too high. In some cases, rather than adjust the camera height, the crew had Foster perform on an eight-inch high wooden box.

Height proved a different challenge when it came to Kristen Stewart. Due to the delays and reshoots to come there was a three inch difference in her height between her first day of shooting and her last. ‘Kristen started out this much shorter than Jodie,’ said visual effects supervisor Kevin Tod Haug, ‘and ended up this much taller.’[18]

Five weeks into production, in March 2001, Jodie Foster requested an immediate meeting with David Fincher and producer Cean Chaffin. Fincher recalled that ‘Jodie walks up, and says, “I’ve got some good news and some bad news.” And before she says anything more, Cean goes, “You’re pregnant! That’s so great!” And I’m like-’ (mimes horrified reaction).[19]

Production continued with the crew using the standard techniques for hiding an actor’s pregnancy on screen: effectively hiding their stomach behind props and set elements. Eventually Foster’s pregnancy grew too obvious to hide, and the remainder of her scenes were scheduled for reshoots once her child was born. ‘The last scene we shot of her is the first scene in the movie, when she’s looking at the house,” Fincher said. “She’s six months pregnant, wearing a huge coat and carrying a ‘Kelly bag,’ which coincidentally was designed to hide Grace Kelly’s pregnancy. [The purse] is held by both hands and perched right in front of her stomach.’[20]

Further reshoots were required when Columbia Pictures executives watched Fincher’s completed footage, and were unhappy with how Foster looked in it.

The Panic Room shoot lasted for 120 days according to some estimates, and as many as 140 according to others. Zodiac, a subsequent Fincher film that covers 14 years of San Francisco history with a sprawling ensemble cast, only took 115 days. Due to the weeks spent keeping parts of the set wet – the film depicts a torrential storm outside – there was a black mold outbreak that required evacuation of cast and crew while it was removed.

The damp, dark sets and the long shoot reportedly strained patience and nerves among the cast and crew. Jodie Foster would later compare shooting the film to going to war: a nightmare at the time, but satisfying once completed. Speaking to Entertainment Weekly after the fact, David Fincher surmised: ‘A lot of people just didn’t respond well to the close quarters. Don’t shoot for 100 days in one place, that’s what’s to be learned from that. Figure out ways not to. They probably had that same kind of problem on The Shining – that’s all in one house. [But] at least they get out, they get to run through a maze.’[21]

Panic Room is a technical marvel to watch for sure, and boasts a crisp, cool sensibility reminiscent of Stanley Kubrick – and subsequently of Christopher Nolan. There is a nuts-and-bolts appreciation to be made of the film: of how Fincher uses the clever, CGI-assisted camera work to give the looming house a palpable physical reality; of how Koepp’s tight and efficient screenplay wrings a maximum of action out of so limited a setting; and of how its cast and dialogue develop such strong, defined characters with such immediacy and clarity.

Right from the beginning the film expresses a blunt, constructed physicality. The opening titles present New York City as an assemblage of architecture, with bold titles rendered in Copperplate like looming metal constructions. They lead the viewer through New York to its specific location, and to the four-story brownstone mansion where they will spend the overwhelming majority of the subsequent feature.

It feels like a stereotype to describe a film’s setting as a character, but its presentation in Panic Room is certainly critical to how Fincher builds tension and tone. It feels dark in places and oppressive, and the manner in which its vaulted spaces are represented give it a rather haunted quality. The house is huge, which only accentuates its inhabitants’ vulnerability when that house is invaded. The entry of the burglars, moving from door to door and window to window from the outside – all captured from within – is marvellously effective. A late moment where a character’s hand becomes trapped in the door of the panic room has a visceral effect. It is something the film’s script earlier assured the viewer could never ever happen due to safeguards, and yet close on the hand it does: it is a house that bites.

The house’s dimensions seem to change as well, driven by the emotion of each scene. Take one sequence in which Meg, taking advantage of the burglars’ absence, runs from the panic room to grab a mobile phone from under her bed. As she reaches under the mattress, the phone can only be a foot or so away – the way the moment is captured the distance looks like metres.

The film has an awful lot to say about class, and how class relates to crime. The three burglars fit rather neatly into upper, middle, and working class. How each responds to the events of the film says something about them, whether it is Junior’s ‘burn to rule’ arrogance or Burnham’s dogged determination to get something he feels is owed to him. It is interesting that the film leaves its most savage interpretation to Raoul – not his real name – who hides behind a mask and presents himself as deeply menacing. He is later revealed to be a bus driver from Buffalo; about as banal as he could get. It is Raoul who pursues the house’s hidden fortune most aggressively, who turns on his partners with murderous efficiency, and who is the one character most damaged by the house itself.

There is a quite shocking cruelty to Raoul, not simply in the casual way he dispenses violence but also who he dispenses that violence to: in one critical moment, and indifferently to popular film convention, he savagely punches a child in the face. ‘I wanted to see her get really smashed,” Fincher explained. ‘I wanted people to know this was not a movie that was going to play nice.’[22]

There is a different sort of class commentary going on with Meg. She clearly married much richer than the class she came from, and what is more she married a much older man than herself. Her ex-husband Stephen is played by Belgian actor Patrick Bachau, an actor 24 years older than Jodie Foster. He has already replaced Meg with a new girlfriend, as well, who is briefly heard over the telephone during the film. In a knowing cameo, the girlfriend is voiced by an uncredited Nicole Kidman.

Meg is visibly inexperienced and uncomfortable with wealth. Her reaction to the panic room itself is telling; ‘the whole thing makes me nervous,’ she admits to the property manager during the film’s opening scenes. She has clearly never negotiated the purchase of a house before. By the film’s conclusion she is selling the house and downsizing back to a more modest lifestyle.

There is also a strong gendered struggle within Meg. She has been betrayed by her ex-husband, and her attempt to assert a new life with her daughter is invaded by three other men. In many ways Meg’s character and Foster’s performance of it resemble her famous award-winning turn as FBI cadet Clarice Starling in Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs. They are both women forced to fight to exist in a domineering, almost misogynistic male world.

David Fincher diminishes Panic Room in comparison to his other films, and he should not. It is a deeply clever work, layering social commentary over a meticulously constructed home invasion thriller. It benefits from a talented cast who work together marvellously. It builds a sense of space in its confined location in a manner few other films have managed.

If nothing else, it would be a deep shame for us to ignore a film that took so much effort and perseverance to complete, and which presented so many unanticipated hurdles and challenges. ‘There was absolutely nothing fun about making the movie,’ Fincher admitted in one interview, before pausing and reflecting for a moment. ‘Nope,’ he said. ‘Nothing.’[23]

We need to reassure the director that it was all worthwhile.

[1] Jeff Jensen, “Cause for alarm: Jodie Foster in Panic Room”, Entertainment Weekly, 15 February 2002.

[2] Xan Brooks, “Directing is masochism”, The Guardian, 24 April 2002.

[3] Tom Davidson, “Panic Room is peak David Fincher”, Medium, 13 July 2020.

[4] Erin Richter, “Panic Room director David Fincher talks shop”, Entertainment Weekly, 15 April 2004.

[5] Jeff Jensen, “Cause for alarm: Jodie Foster in Panic Room”, Entertainment Weekly, 15 February 2002.

[6] Erin Richter, “Panic Room director David Fincher talks shop”, Entertainment Weekly, 15 April 2004.

[7] David Koepp, Panic Room, Columbia Pictures, 2002.

[8] Leo V, “David Koepp: ‘We’re all very inspired by Steven Spielberg, but nobody can imitate him. That’s his particular gift’”, Film Talk, 20 May 2018.

[9] Xan Brooks, “Directing is masochism”, The Guardian, 24 April 2002.

[10] Dana Calvo, “Opening a door to panic rooms”, Los Angeles Times, 27 March 2002.

[11] Allyson Shiffman and David A. Keeps, “New again: Jared Leto”, Interview, 29 October 2013.

[12] Wilson Morales, “Panic, not me: an interview with Forest Whitaker”, Black Film, March 2002.

[13] James Mottram, “Forest Whitaker: Panic Room”, BBC Films, 28 March 2002.

[14] Daniel Robert Epstein, “Inside Panic Room : David Fincher, the Roundtable Interview”, Davidfincher.net, 2002.

[15] Tom Davidson, “Panic Room is peak David Fincher”, Medium, 13 July 2020.

[16] Brie Stimson, “Nicole Kidman reveals she was ‘having a breakdown’ when she pulled out of hit movie”, News.com.au, 31 May 2024.

[17] David M. Halbfinger, “Lights, bogeyman, action”, New York Times, 18 February 2007.

[18] Ian Failes, “David had the picture of the movie in his head”, Befores & Afters, 30 March 2022.

[19] Jeff Jensen, “Cause for alarm: Jodie Foster in Panic Room”, Entertainment Weekly, 15 February 2002.

[20] Dana Calvo, “Opening a door to panic rooms”, Los Angeles Times, 27 March 2002.

[21] Erin Richter, “Panic Room director David Fincher talks shop”, Entertainment Weekly, 15 April 2004.

[22] Ryan Gilbey, “Four walls and a funeral”, The Independent, 19 April 2002.

[23] Ryan Gilbey, “Four walls and a funeral”, The Independent, 19 April 2002.

Leave a comment