In Hollywood, there are no guaranteed recipes for success, but there do seem to be a lot of recipes for failure. One of the more obvious ones in 1995 was this: take a popular science fiction short story, add an artist as first-time director, add $25 million dollars, have your lead actor become Hollywood’s biggest box office draw during the shoot, then stand back and wait for the studio interference.

The result is Johnny Mnemonic, the first of five virtual reality or Internet-themed movies that plagued cinemas in 1995. It was followed over the next few months by Virtuosity, The Net, Hackers and Strange Days. Precisely one of these movies was really good, and it wasn’t Johnny Mnemonic.

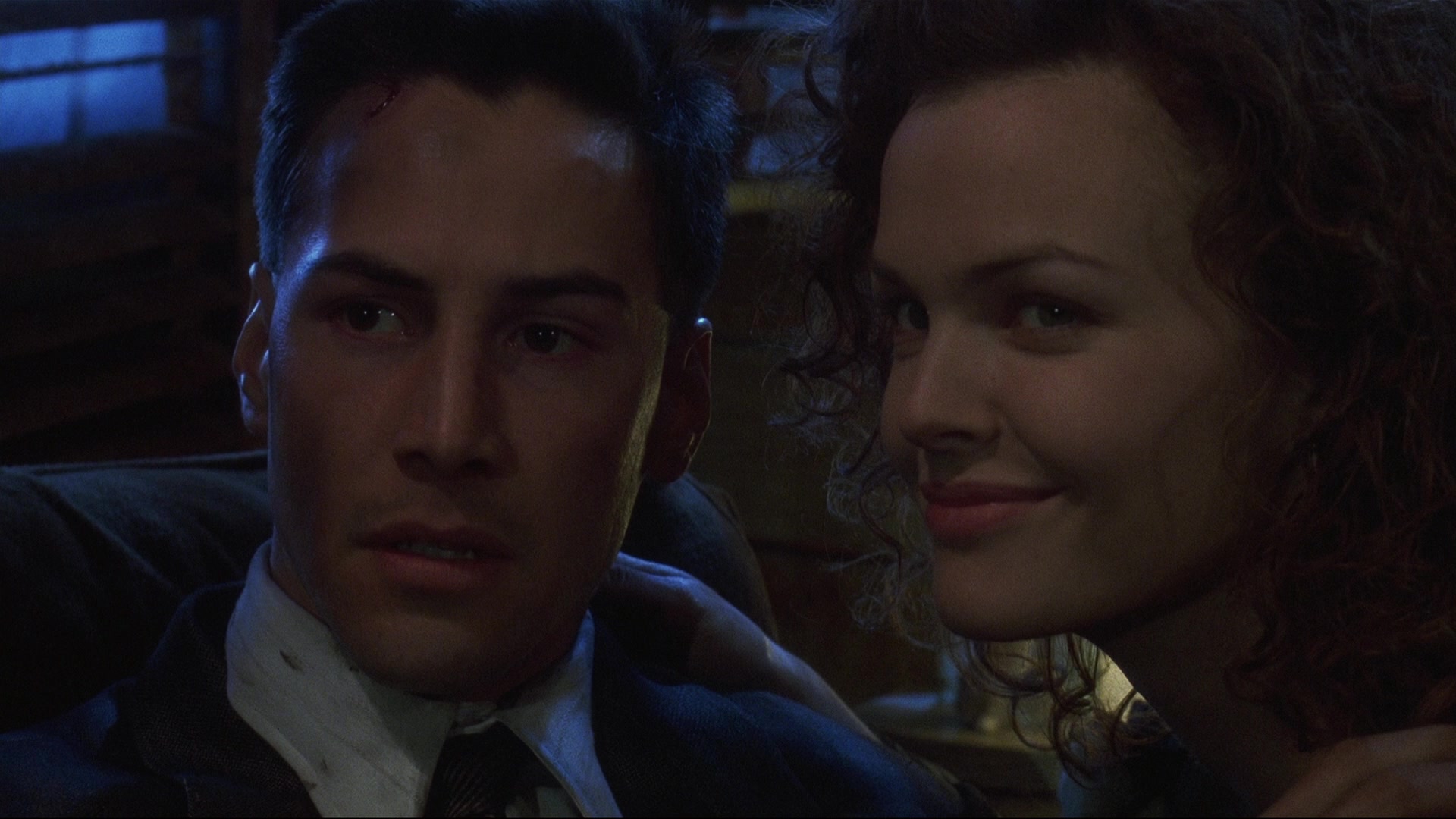

Johnny Mnemonic is set in 2021, where the world appears to consist entirely of dirty back alleys and nightclubs, and everything on the planet is either owned by or on the run from a massive corporation. Johnny (Keanu Reeves) is a specialised courier who carries computer data downloaded into his own brain. After overloading his brain with a mysterious 160 gigabyte file, Johnny has twenty-four hours to get the data out of his brain before it fries his mind for good. All the while he is on the run with a drug-addicted bodyguard (Dina Meyer) from the yakuza, who have been hired by a pharmaceutical corporation to retrieve his head – and the data within – at any cost.

The film forms part of a particular sub-genre of science fiction known as cyberpunk. Cyberpunk was a peculiarly 1980s phenomenon involving computer technology, fears of the over-corporatisation of human society and a sort of backstreets grass-roots resistance to those corporations. In terms of visual imagery the genre made its first significant impact with Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner in 1982. In terms of literary ideas, cyberpunk formed as a coherent sub-genre on the back of William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer.

When Neuromancer became a best-seller, Hollywood producers were quick to scour Gibson’s back catalogue of literary works to find some way of translating that literary success to the movies. Neuromancer itself was optioned and then lost in development. It’s still out in the industry somewhere: every few years another eager director announces an adaptation of Neuromancer as his or her next project, only to have the production vanish before it even enters pre-production. When this essay was first written, a new attempt was underway by writer/director Vincenzo Natali (Cube, Splice). At the time of reprinting – some 20-odd years later – it is rumoured that Apple+ may be bankrolling a serialised adaptation.

Carolco Pictures optioned “Johnny Mnemonic”, a 1980 short story by Gibson. It had a lot in its favour over Neuromancer. For one thing it was shorter, and its plot was more streamlined. It’s a cliché that short stories adapt better into motion pictures than novels, but it’s a cliché because it’s generally true.

Carolco spent several years shipping Johnny Mnemonic to all of Hollywood’s major studios, only to be turned down each time. When Carolco started to experience financial difficulties, and shed many of its optioned properties to the highest bidder, art collector and occasional film producer Staffan Ahrenberg picked up the rights at a bargain rate. Ahrenberg then partnered with producer Peter Hoffman – a former production executive at Carolco – to attempt bringing Johnny Mnemonic to fruition as an independent feature.

Hoffman and Ahrenberg found an unusual director for the project in the form of artist Robert Longo. Johnny Mnemonic would be his first – and, to date, only – motion picture. ‘Well, there’s a Kurt Vonnegut quote I like,’ Longo explained shortly before the film’s release, ‘something about when you pretend to be someone long enough, one day you’ll be that person. I was hoping that’d be true of this experience. ‘Cause all of a sudden I’m directing a movie and quietly going, “Wait a minute, I really don’t know how to do this! Holy shit, where do we put these cameras?” It’s like waking up out of a dream and realizing you’re riding a bike without any handlebars.’1

Longo’s career had been primarily based in painting and sculpture, although he had directed a number of music videos including REM’s “The One I Love” and New Order’s “Bizarre Love Triangle”.

Despite being new to motion pictures, Longo had a strong handle on how he perceived Johnny Mnemonic’s science fiction elements. ‘The future is not something I’m really interested in,’ he said. ‘What I’m interested in is using it to talk about now. I think it’s the same with William. Johnny Mnemonic is just an extreme version of now.’2

Longo and Gibson first met face-to-face and resolved to bring Johnny Mnemonic to the big screen together – Longo directing and Gibson adapting his own story. Gibson had already had some experience writing for film, including screenplays for a proposed Alien III and an adaptation of his short story “New Rose Hotel” for director Kathryn Bigelow, although neither project had entered production. (In the end, while both Alien 3 and New Rose Hotel were produced, neither film used Gibson’s screenplay.)

Longo and Gibson’s idea for Johnny Mnemonic was a low budget arthouse piece, shot in black and white and self-consciously emulating the performance styles of science fiction cinema. Their anticipated budget was somewhere between one and one and a half million dollars.

As Carolco had already discovered, no studio in North America was interested in bankrolling a low budget black and white science fiction film. It was only when the production was completely overhauled into a full colour, far more expensive proposal that Hollywood sat up and took notice. ‘We went in and asked for a million and a half,’ said Gibson, ‘and they laughed. It wasn’t until we started asking for much more that they started taking it seriously.’3

With a massively increased budget, Johnny Mnemonic was now under enormous pressure to find a bankable star to play the title character. After considering Christopher Lambert, Hoffman and Longo managed to pique the interest of Val Kilmer. The film was entering the pre-production phase in 1993 when Kilmer unexpectedly withdrew from the project, having been offered the chance (and a lucrative pay cheque) to replace Michael Keaton as Batman in Joel Schumacher’s Batman Forever. Kilmer’s departure was something of a relief for Robert Longo, who had already been fighting the actor over what sort of characterisation Johnny would have.

At the last minute Keanu Reeves agreed to replace Kilmer. He had just completed shooting the action film Speed for 20th Century Fox, and was looking for another project to jump into. Not only was Reeves familiar with Longo’s artistic work – and liked it – he was also a fan of William Gibson. Reeves was paid $2 million to play Johnny – industry insiders estimated that had he waited until Speed’s release to sign the contract, he could have asked for four times as much.

‘I remember working on Johnny Mnemonic,’ said Reeves. ‘It was right after finishing Speed, which was very physical and demanding. And Johnny Mnemonic turned out to be a very intense, quick shoot. I was in every scene. And I remember being so… l could quantify the energy it would take to get up off of the couch. I was trying not to move so that I could save my strength. But it was great, and I felt very alive.’4

With a Canadian star and writer, Staffan Ahrenberg and Peter Hoffman were able to take advantage of Canadian tax breaks and bring Johnny Mnemonic to the screen at a reduced budget. The final film cost $25 million to produce, with the money borrowed from 19 separate investors, production houses and backers.

Because of the wide variety of financial backers involved in producing the film, each of whom was generally based in a different country, Johnny Mnemonic rapidly found itself with an international cast. Each actor was specifically cast to satisfy a contract with one of the 19 funding bodies – and to make the final film easier to sell in their home country. Udo Kier was cast to make the Germans happy, Dolph Lundgren the Swedes, and Takeshi Kitano the Japanese.

Takeshi Kitano seems an oddity among the film’s already unusual cast. The former comedian had established himself not only as one of Japan’s pre-eminent dramatic actors, but also one of its most talented directors as well. ‘We knew he wanted to make an American movie,’ said Longo, ‘but I had to go see him. I went to meet him after I did a museum show in Korea and I ended up going to his house for dinner. His agents and his managers had never been to his house. They came along but he made them sit in a closet while we had dinner. That night he gave me this beautiful vase. The next day his manager called me and said that when I took it through customs I shouldn’t tell them Takeshi gave it to me: “Just tell them you bought it in a shop, because it was made by one of the National Treasures”.’5

‘Takeshi’s a big star in Japan,’ said Hoffman, ‘and the Japanese distributor wanted to see more Takeshi, so I made a deal.’6 The Japanese edit of Johnny Mnemonic was eight minutes longer than the edit seen in the rest of the world. All eight minutes featured Takeshi, all of them independently funded by the Japanese distributor.

Takeshi Kitano had already made one English-language film, Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence, but he found his second attempt far less enjoyable. ‘Johnny Mnemonic was a nightmare,’ he said. ‘I felt like a child invited to Disneyland. I was pleased that I got the chance to visit the real Disneyland. But I returned to Japan without being able to ride on any of the attractions.’7

Popular hip hop performer Ice-T played the role of J-Bone, a pivotal figure in the anti-corporate resistance. ‘When Ice-T agreed to do the movie I was very happy,’ said Gibson. ‘My anxiety was that I would have to write dialogue for this guy, and I knew that whatever he would do would probably be better. So we gave him an unusually free reign on his dialogue, and he came up with some really wonderful stuff.’8

Musician and actor Henry Rollins played Spider, a backstreet medic and resistance fighter. ‘I’m not a fan of cyberpunk,’ Rollins admitted, ‘it doesn’t interest me at all because I like terra firma human dramas. I like the things that go on in this movie though, and I wanted to work with Robert because I like his art.’9

Dina Meyer played Jane, a Newark bodyguard suffering from a 21st century neurological disease. The character was created by Gibson for the movie, and replaced the original character of Molly Millions – who had later appeared in Neuromancer. The continuing attempts to get a Neuromancer movie produced made it impossible for Molly to be incorporated in the film of Johnny Mnemonic, so Jane acted as a replacement.

Dolph Lundgren played the Street Preacher, a deranged priest who sidelines as a bounty hunter. Lundgren had initially trained as a chemical engineer (he holds an MA from the University of Sydney) before briefly appearing in the 1985 James Bond film A View to a Kill. His big break came later in the same year, starring opposite Sylvester Stallone in the boxing sequel Rocky IV. From then on Lundgren had forged a successful career starring in low-to-mid-range action movies, including Masters of the Universe (1987), The Punisher (1989) and Universal Soldier (1992).

The film was shot on location in Toronto and Montreal, and on soundstages erected in a converted Toronto factory. The shoot lasted 12 weeks in total.

Despite being shot in Canada, Johnny Mnemonic’s story was divided between Beijing and a re-envisaged Newark, New Jersey. ‘The free city of Newark is like the Wild West,’ said Gibson, ‘the government’s gone bankrupt, and the only law that’s left is the Yakuza. It’s not the Third World… it’s the Fourth World. It’s America’s conceptual nightmare on the brink of a new century, a savage experiment in social Darwinism where God seems to be a bored lab worker with his thumb permanently on technology’s fast forward button.’10

The sets were designed by industrial designer Nilo Rodis-Jamero. ‘This is a low budget movie with an ambition to be bigger,’ said Longo. ‘I had a great production designer, Nilo Rodis-Jamero, who knew my work. I gave him a lot of art books to look at, while he made me always aware that I was making a low-budget movie. I wanted to make a clunky movie. I didn’t have the time to make, and because I had a lot of people to deal with, I didn’t want to make an overtly stylish movie. I didn’t want to make an MTV movie.’11

Rodis-Jamero said: ‘I’ve focused on three parts of the film that make crucial statements as to what the future is. The first is the upload device, which gives us a sense of the advanced technology and its place in society and the world. The next one is when Johnny and Jane rifle through a video computer store, which is another statement about the increased sophistication of hardware which is imminent. And finally, I’ve focused on the LoTeks’ hardware, which represents where we’ve been. The design of this film reflects a philosophical view of the future as well as a very strong visual statement on where we could be headed.’12

The largest set constructed for the film was “the Bridge”, a makeshift community constructed out of industrial debris that hangs underneath an abandoned road bridge. Gibson ripped the setting, which did not appear in the original short story, from his own novel Virtual Light. ‘At the time,’ he said, ‘I didn’t think that I’d have a chance to do anything else. I saw Johnny Mnemonic as I wrote it, and we shot it as a collage of a lot of things. It was about a particular kind of science fiction. It’s not about Virtual Light but about that sort of environment. The set that Longo constructed was stunningly great, and the cut that emerged – you scarcely get any sense of it. It was probably one of the most beautifully realised science fiction sets since Blade Runner. Really, really great. And as we shot it, the film made considerably more use of it, but it did not make it to the screen.’13

When recollecting his experience during the shoot, Robert Longo said: ‘I found the whole experience of making this picture vaguely unsettling – but comical, too. For instance, a lot of times, directing a movie is explaining to the actors what you want them to do, and then actually doing the gestures, which is really weird. You’ll say stuff like, “Walk across the room like this”, to seasoned pros, and then you’ll show them what you mean, with 50 people standing around looking at you like you’re a fucking idiot.’14

Dolph Lundgren was one actor who appreciated Longo’s fresh approach: ‘He wasn’t as set in the same way of working, which sometimes can cause delays in the shooting. On the other hand, it was inspiring for me creatively because he hadn’t set his way on anything almost, as far as performers went or blocking. It gave me a lot of room to work on my character.’15

William Gibson said: ‘We were looking for something that conveyed more a sense of nostalgia for the future than a futuristic look. The world of Johnny Mnemonic is a world where the capital F future isn’t going to arise, which I think is pretty much our situation in 1995: we’ve given up on The Jetsons.’16

In one key moment of the climax, Johnny angrily breaks down and enters a lengthy rant about how much he is missing the modern conveniences he is used to – conveniences he can’t take advantage of while running away from the yakuza in back alleys and junkyards. His furious monologue, which is almost certainly the most entertaining moment of the film, did not feature in the original screenplay at all. According Gibson, Keanu Reeves ‘looked at his lines for that scene and said, “This is dull,” so I went back to my room and stayed up until four in the morning writing it.’17

‘We called this scene “The Little Prince” speech,’ said Longo. ‘We shot it and didn’t tell anyone about it, the studio didn’t know. The other versions of the scene were even more insane. Rather than having this gradual insanity he was totally schizzed out, going totally nuts. This Johnny Mnemonic is like Gibson on steroids.’18

There is a good chance that had Speed not been a commercial hit, Johnny Mnemonic might have made it to cinemas in the form that Longo and Gibson intended. With the unexpected success of Speed, however, TriStar Pictures found themselves in the position of distributing Keanu Reeves’ next movie. The opportunity to ride on Speed’s coat-tails with another action movie was too great to resist.

TriStar first started exerting pressure on Longo and the production crew during the shoot, suggesting the film incorporate additional action sequences and gunfights. While their interference was largely resisted during the shoot, when it came to post-production it was another matter. ‘Basically what happened,’ Gibson explained to Wired, ‘was it was taken away and re-cut by the American distributor in the last month of its pre-release life, and it went from being a very funny, very alternative piece of work to being something that had been very unsuccessfully chopped and cut into something more mainstream.’19

In a later interview, Gibson was more reflective on the experience. He said: ‘After a certain point, the suit who was most supportive of us throughout the process – he would speak to my position by saying, “At this point I have to speak for the members of our audience who are ‘Gibson-challenged’” – and at that point I knew that I was in trouble. This guy was saying that “whatever it is you’re laying down here, bud, they ain’t going to get it.” He was just doing his job.’20

With an eye to releasing a commercial hit with mainstream appeal, TriStar’s editors went about removing any potentially objectionable content from the film. Lengthy dialogue was cut out to keep the film rattling along at breakneck pace. Elements of the back story were excised, in the belief that an audience watching an action film didn’t need to understand the minutiae of the plot.

TriStar even forced the production to re-shoot key sequences, in an attempt to make Johnny more likeable. They also objected to the film’s ending, in which Johnny would voluntarily die to allow the cure for NAS to be recovered from his brain. ‘For three and a half months,’ Keanu Reeves said, ‘I played a character who didn’t consciously want his memory back, so six months later we re-shoot a scene where I say: “I want it all back”, which goes at the beginning of the film, and then at the end of the film, where my character used to make the ultimate sacrifice and offer up his life so that the world can have this cure, instead he ends up in this stupid virtual reality world where this big fish ends up trying to save me and mankind.’ The experience irreparably soured Reeves’ opinion of the film. ‘Oh my gosh,’ he said, just two months after the film’s release, ‘let it crash and burn!’21

The original score to the film, by Mychael Danna (Exotica, The Sweet Hereafter), was abandoned by TriStar and replaced against Longo’s wishes with a last-minute score by Brad Fiedel (The Terminator). The Japanese edit of the film retained Danna’s original score, along with most of Longo’s original intended edit.

The most savagely cut element of the film was Dolph Lundgren’s deranged preacher. Lundgren had originally signed onto the film to demonstrate his acting range, and was particularly proud of a lengthy and impassioned monologue his character delivered on the evils of technology. By the time Johnny Mnemonic reached the cinemas, the monologue was gone – as were the vast bulk of Lundgren’s scenes. An actor who worked on the film specifically to escape being seen as a violent thug now found himself playing exactly that – and a faintly ridiculous thug at that.

TriStar Pictures scheduled Johnny Mnemonic for the lucrative Memorial Day weekend, figuring that Keanu Reeves’ popularity would be strong enough to compete with whatever else was released. ‘Little did we know,’ said producer Don Carmody, ‘that Die Hard would open then too.’ 22

Released on just over 2,000 screens, the film brought in $8.9 million over its opening weekend: nowhere near as much as TriStar had hoped for, but by no means a total disaster. It faced extremely strong opposition from fellow new releases such as Casper (which opened at #1) and Braveheart (which opened at #3), as well as the aforementioned Die Hard sequel, which performed very strongly in its second weekend to take the #2 position. Johnny Mnemonic was forced to make do with sixth place, behind Crimson Tide and Forget Paris.

The film pulled in an addition $4.7 million in its second week, slipping one place to #7. By its fourth week it had slipped out of the Top 10 altogether. By the end of its theatrical run, Johnny Mnemonic had grossed just over $19 million dollars in the USA. The film was, technically speaking, a flop.

The critical response to the film was fiercely negative. Entertainment Weekly’s Owen Gleiberman wrote: ‘Johnny Mnemonic, a slack and derivative future-shock thriller (it’s basically Blade Runner with tackier sets), offers the embarrassing spectacle of Keanu Reeves working overtime to convince you that he has too much on his mind. He doesn’t, and neither does the movie.’ 23

In Variety, Todd McCarthy wrote: ‘Absolutely zero human interest is generated by Reeves, who comes off as gruff, hostile and selfish, all in one dimension. Most of the other cast members are seen to equal disadvantage, though not at such length.’24

Roger Ebert was a little more conciliatory, as he often is, noting that ‘Johnny Mnemonic is one of the great goofy gestures of recent cinema, a movie that doesn’t deserve one nanosecond of serious analysis but has a kind of idiotic grandeur that makes you almost forgive it.’25

‘Johnny,’ wrote Brian D’Amato in Art Forum, ‘is a $26 million movie that looks like a $60 million movie.’ 26

When the film finally reached British cinemas in February 1996, the London critics were not any more kind. In The Daily Mail, Christopher Tookey wrote: ‘Towards the long-awaited end, Keanu’s head is saved from exploding by a kindly dolphin. By this stage, I was wondering if Keanu was the only person on this movie suffering from synaptic seepage.’27

The professional critics regularly tell just one side of a story, and it’s all too easy in the face of a flawed or troubled film production for them to circle the movie like wolves, each trying to develop the catchiest witticism with which to drag the film down. In the case of Johnny Mnemonic, the critics were – at least while taking the film at face value – dead on the money.

There are several major problems with Johnny Mnemonic, and the fact that these problems are each overlayed on top of each other serves to compound the film’s faults. Let’s do our best to tackle them one at layer of mistakes at a time.

First and foremost, this is a film that has suffered what most almost be the maximum amount of damage that studio interference could inflict. A serious science fiction film has been buried by too tight an edit. The characters and the narrative have no room to breathe, because the studio-enforced edit is too desperate to drag its audience to the next action scene. This action-orientated edit creates a major problem, because it’s clear from watching it that Johnny Mnemonic is not an action film. What moments of gunplay and physical combat exist are directed in a brief, to-the-point manner. Longo was clearly not interested in making an action film, and as a result no amount of editing by TriStar Pictures is going to change that. Just like you can’t make a chicken sandwich without some pieces of chicken, it’s impossible to edit an action film if the action simply isn’t there.

The editing makes the film slightly confusing as well. The action moves from the USA to Beijing so suddenly it’s easy to fail to realise the action has moved at all. Character motivations become murky, and difficult to understand. The pace feels completely wrong, so that despite being barely more than an hour and a half in length, the film drags as if it’s twice that long.

The studio-enforced reshoots and edits make a mockery of the characters. It is little wonder that Reeves’ performance feels so inconsistent and erratic: his motivations were changed halfway through making the movie. Despite a widespread belief, Keanu Reeves is – when directed well – a very strong, engaging actor. When trapped as the lead in a film like this, he is left in the unfortunate position of seeming to prove his naysayers correct.

Dolph Lundgren’s scenes have been almost completely excised, making the ranting bearded psychopath that remains oddly inexplicable – and regularly unintentionally funny.

Of course, underneath all of the studio’s problems, there is also the basic reality that Johnny Mnemonic is not a well-directed film. The actors feel under-directed, sometimes over-emoting scenes, sometimes under-emoting them, and in the case of Takeshi Kitano simply looking bored and vaguely disappointed. Despite the best efforts of TriStar’s editing, there is no sense of urgency to the film, and no sense that Longo – despite being a talented artist – has a visual eye for the film image. There is one oddly artistic moment in the film, which comes very early on. In a Beijing hotel lobby, Johnny looks into a massive fish tank. The curved glass distorts his head, making it look like the top of his skull has simply trailed away into infinity. It’s nicely symbolic of the character, and the plight he finds himself in. The scene also provides Johnny with his one moment of genuine emotion and character, warmly waving to a small girl on the other side of the fish tank. One moment of artistry and warmth in a 96 minute movie makes for a fairly dry viewing experience.

The sets have been put together with some thought and imagination, but the problem is that they all look like sets. There is no sense of reality to Johnny’s environment. They feel oddly like the sorts of sets you’d see in a theatrical play, where the audience is expected to fill in the suspension of disbelief. In cinema that expectation simply isn’t there, and it makes Johnny Mnemonic a fairly artificial experience.

Finally, beneath the studio interference and the inexperienced direction, there is also the inescapable problem that William Gibson simply didn’t write a particularly good screenplay. All of the elements of the cyberpunk genre are there, along with plenty of the ideas and concepts that make Gibson the poster child for that movement. On the other hand, the elements feel mechanical. They feel outdated. By the time Johnny Mnemonic was released in cinemas, its source story was 15 years old. Gibson himself had already moved onto more complex and interesting ideas in novels such as Virtual Light, whereas contemporaries such as Neal Stephenson and Bruce Sterling had produced their own engaging, idea-filled works. By comparison Johnny Mnemonic feels like yesterday’s news.

The biggest problem is that the story simply doesn’t say anything. There is so much potential in investigating what sort of person would voluntarily remove their own memories in order to work as an information courier. What effect would it have on their life? How do our own experiences shape the people we are, and what happens to us if those experiences are taken away? While it is possible these questions might have been explored without TriStar’s interference, based on the film that is left it’s quite difficult to believe that they would have been.

Arthur and Marilouise Kroker hit the nail on the head when they wrote: ‘The movie suffers the very worst fate of all: it’s been normalised, rationalised, chopped down to image-consumer size, drained of its charisma and recuperated as a museum-piece of lost cybernetic possibilities.’28 They wrote that sentence in what would seem to be an accurately named chapter: “Johnny Mnemonic: The Day Cyberpunk Died”.

- William Gibson, Robert Longo, “Remembering Johnny”, Wired 3.06, June 1995.

- Mo Ryan, “Data Storm”, Cinescape, June 1995.

- Gibson, Longo, 1995.

- Margy Rochlin, “Keanu Reeves: The US Interview”, US, March 1995.

- Manolha Dargis, “Cyber Johnny”, Sight and Sound, February 1996.

- Chris Nashawaty, “What Made Johnny Run”, Entertainment Weekly, 23 June 1995.

- Jim Hoberman, “The Ultimate Renaissance Man”, Village Voice, March 1998.

- Quoted in Johnny Mnemonic production notes, TriStar Pictures, 1995.

- Kristine McKenna, “It’s Just Art on the Big Screen”, Los Angeles Times, 21 May 1995.

- Johnny Mnemonic production notes, 1995.

- Dargis, 1996.

- Johnny Mnemonic production notes, 1995.

- Uri Dowbenko, William Gibson: Prophet of Cyber-Grunge, Steamshovel Press, 2000.

- Gibson, Longo, 1995.

- Louise A. Barile, “Holy Fire”, Starbase, No. 33, 1995.

- Dargis, 1996.

- Stephen Schaefer, “Will Power”, Entertainment Weekly, 16 June 1995.

- Dargis, 1996.

- Ben Lincoln, “William Gibson: The Cyberpunk Speaks”, The Peak, 19 October 1998.

- Dowbenko, 2000.

- Paul Fischer, “From Walking in the Clouds to Cyberspace”, Burst Films, August 1995.

- Nashawaty, 1995.

- Owen Gleiberman, “Johnny Mnemonic”, Entertainment Weekly, 9 June 1995.

- Todd McCarthy, “Johnny Mnemonic”, Variety, 21 May 1995.

- Roger Ebert, “Johnny Mnemonic”, Chicago Sun-Times, 26 May 1995.

- Brian D’Amato, “Electric I”, Art Forum, Summer 1995.

- Christopher Tookey, “Keanu clueless in cyberspace”, The Daily Mail, 9 February 1996.

- Arthur and Marilouise Kroker, eds. Hacking the Future, St Martin’s Press, 1996.

Leave a comment